Edinburgh-born scientist wins Nobel Prize for chemistry

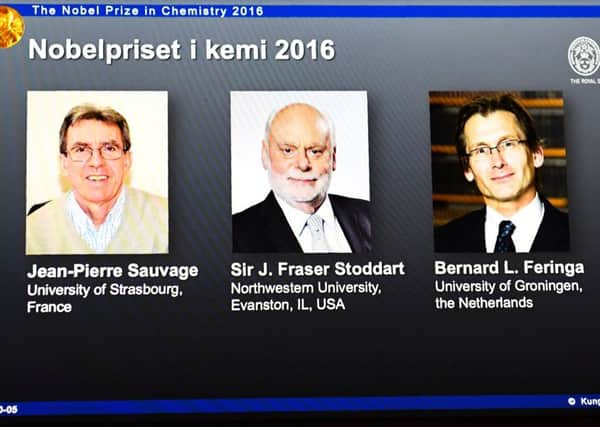

Sir James Fraser Stoddard, 74, from Northwestern University in Illinois, was named joint winner of the prestigious award in recognition of his work on tiny motors too small to see with the naked eye.

The other two laureates announced at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm were Professor Jean-Pierre Sauvage from the University of Strasbourg, France, and Professor Bernard Feringa, from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEach scientist will receive an equal share of the eight million kronor (£733,000) prize money.

The three men played pivotal roles in overcoming the huge challenge of building controllable microscopic machines incorporating atomic-scale rods, rotors and ratchets.

Sir James obtained a PhD from the University of Edinburgh and worked in Sheffield and Birmingham before moving to the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1997.

He was included in the Queen’s New Year’s honours list in 2006 and made a knight bachelor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe award, announced by Professor Goran Hansson, secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, was “for the design and synthesis of molecular machines”.

Each of the molecular devices created by the scientists is more than 1,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair.

Yet, magnified up, they operate much like large-scale machinery with rings spinning round axles, components moving to-and-fro along tracks, “elevator” platforms that rise and fall, and artificial contracting “muscles”.

Prof Feringa’s research group has even demonstrated a four-wheel drive “nanocar” with a molecular chassis and motors that function as wheels.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFuture applications of the nanotech devices still remain largely in the realm of science fiction. But they could include tiny medical devices that circulate through the bloodstream cleaning arteries, delivering drugs or performing microsurgery in an echo of the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage.

Groups of molecular machines operating together may also provide the basis for self-assembling structures or synthetic proteins.

Speaking at the awards press conference, Nobel committee member Professor Olof Ramstrom, a nanotechnology expert from the Royal Institute of Chemistry in Stockholm, said: “This is basic fundamental science .. You can say that the development stage here is similar to what it was at the beginning of the 19th century when many scientists demonstrated different electrical machines.

“Of course these electrical machines from the beginning of the 19th century, they created a revolution. Nowadays we have electrical machines everywhere.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Sara Snogerup Linse, from the University of Lund, who chairs the Nobel chemistry committee, said molecular machines are an “exploding field” around the world.

“This is the start of a new molecular era,” she said. “We think this is a very right time to award this Nobel Prize because this is when it takes off towards the applications.

“We can only guess, but smart materials for sure will come; materials that can change shape or function or properties when you, for example, shine a light on them.”

She did not think there was anything to fear from the rise of molecular machines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I think they’re mainly a big promise,” said Prof Linse. “They don’t have this property of self-replication so they can’t take over. They are all controlled by an energy input, so if you don’t want them to do something you can just stop the energy input and they will stop working.”

Yesterday, Scottish-born scientists David Thouless and Michael Kosterlitz were awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in physics, for work that “revealed the secrets of exotic matter”.