Mystery of the child's bones hidden in Edinburgh Castle walls - Part 1

Since it was well known that Mary Queen of Scots had given birth to the future James VI in these very apartments, this extraordinary discovery would imply that the true child of Mary had died in infancy, and that the little prince was a changeling introduced into the royal crib.

Various conspiracy theorists have speculated that the Earl and Countess of Mar donated their second son to act the part of the little prince, or that an empty crib had been lowered from the Castle using a long rope, to be filled with a healthy child purchased for a few shillings in one of the dens in the Cowgate; in contrast, the mainstream historians have shunned the story as a fabrication, invented by the tour guides to astound their credulous visitors.Interestingly, some research demonstrates that the story of the ‘Edinburgh Castle Mystery’ has more truth behind it than previously presumed. The Archives of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland hold some very interesting early documents concerning this mysterious matter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

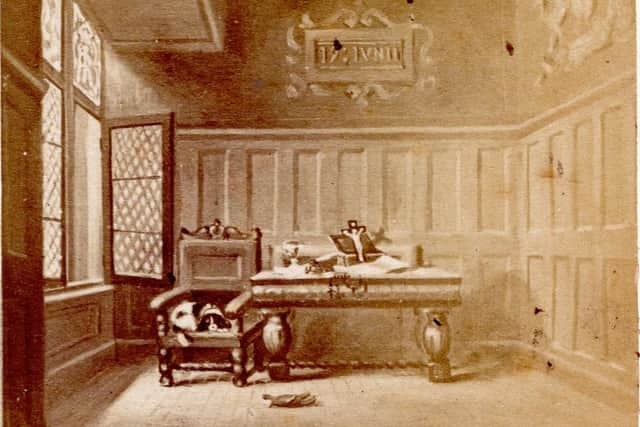

Hide AdAt the meeting of February 14 1831 an account by Captain JE Alexander was read, about the ‘discovery in the wall of the ancient Palace of the Castle of Edinburgh, of the remains of a child, which were wrapped in a shroud of Silk and Cloth of Gold, having the letter ‘J’ embroidered thereupon.’

A rib and some other bones from the child were presented to the Society, by the Rev James Chapman of Edinburgh Castle, at the same meeting. Part of the shroud, having the letter ’J’ embroidered on it, and belonging to Mr D’Alton of the 71st Highland Light Infantry, was also exhibited.

In a letter dated July 16 1831, Sergeant Major Dingwall, late of the Scots Grey, sent a part of the coffin and some bones to the Society, adding the valuable detail that they had been found on August 11, 1830.

The 1849 catalogue of the Society’s museum does not mention either coffin or bones, but instead includes a portion of the shroud in which the remains of the infant had been wrapped, donated by Alexander. This item has since been lost.Since there is also mention of the mysterious discovery at Edinburgh Castle in a contemporary newspaper, the Glasgow Courier of August 14 1830, there is good reason to believe that on August 11, 1830, a wooden box or coffin containing bones presumed to be human were found in the Royal Apartments of the Castle. Portions of the coffin, shroud and bones were taken as souvenirs by several of the military men; some of these exhibits ended up with the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, who have lost or discarded them long ago. Several of the accounts mention that the shroud was embroidered with the letter ‘J’ or ‘I’; some people thought they could also see a ‘R’.The account of the discovery in the Glasgow Courier is worth giving in full:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad'On Wednesday last, as the masons were knocking off the loose lime, previous to re-casting the old palace in the Castle, they discovered a hole in the wall. The workmen described it as being three feet and a half long, one foot two inches high and one foot in breadth.

'Between the end of the opening and the surface of the wall (it is the front of the palace) there was a stone about six inches thick and about the same length which was supposed, from the thickness of the wall, to be between the extremity of the opening and the inner surface of the wall or room.

'In this cavity was found several human bones, some pieces of oak supposed to have been parts of a coffin, and bits of woollen cloth, in all probability the lining of it. On the lining the letter J was distinctly visible, and some of the masons said they saw the letter G also.

'The bones appear to have been those of a young child. Some of them are in the possession of the person from whom we received this communication. It is right to add that the opening was across the wall.'

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne would have thought that such a remarkable discovery, near the room where Mary Queen of Scots had given birth to her son and heir back in 1566, would have been given widespread attention among those of a historical bent, but this was not the case.

In 1832, Charles Mackie’s guidebook to Edinburgh Castle placed the discovery of the coffin to the wall between the Crown Room and the west entrance into the square; he improved on the story to claim that the coffin had contained the bones of a child and fragments of velvet with the initials ‘JR’, preserved by the officers of the 71st regiment, who were then stationed at the Castle...

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is an edited extract from Jan Bondeson’s book Phillimore’s Edinburgh, published by Amberley Publishing

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.