18th century adverts for runaway slaves shared in online database

More than 800 advertisements for runaway slaves, collected from 18th century British newspapers, have now been shared online, allowing the public to find out more about one of the darkest chapters in the country’s history.

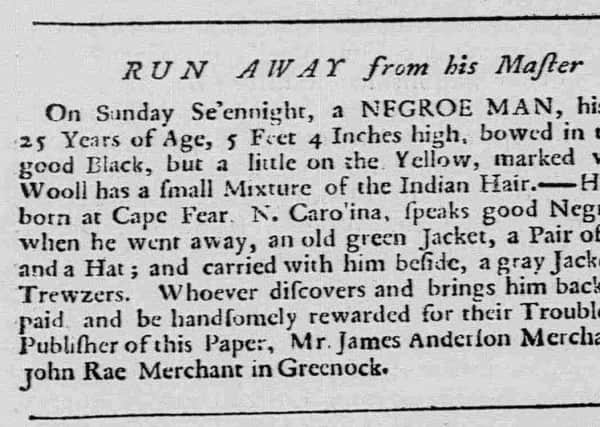

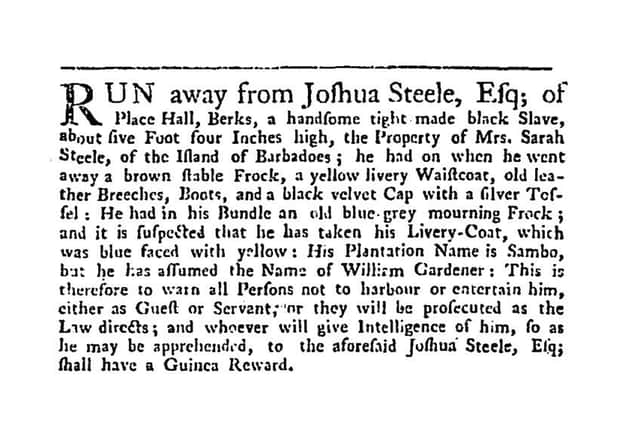

The adverts were originally placed by masters and owners offering rewards to anyone who captured and returned the runaways. The buying and selling of slaves was made illegal across the British Empire in 1807, but owning slaves was permitted until it was outlawed completely in 1833.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new database is the result of work by academics at the University of Glasgow as part of the Runaway Slaves project.

They found that most runaways were of African descent, though a small number were from the Indian sub-continent and a very few were Indigenous Americans.

The advertisements provide rich source of information about the enslaved and slavery in 18th century mainland Britain, with the notices describing the mannerisms, clothes, hairstyles, skin markings, and skills of people who otherwise would have been completely absent from the official historical records of the time.

They also include information about the work of the enslaved, their homes and situations, and the lives, businesses and homes of their masters and mistresses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of the runaway slaves were employed as sailors and dock workers, but the large majority were domestic servants and workers in the households of elite and mercantile families who had spent time in or had connections with the British Empire’s colonies.

An advert from the Edinburgh Evening Courant, dated February 13, 1727, stated: “Run away on the 7th instant from Dr Gustavus Brown’s Lodgings in Glasgow, a Negro Woman, named Ann, being about 18 Years of Age, with a green Gown and a Brass Collar about her Neck, on which are engraved these words [“Gustavus Brown in Dalkieth his Negro, 1726.”] Whoever apprehends her, so as she may be recovered, shall have two Guineas Reward, and necessary Charges allowed by Laurence Dinwiddie Junior Merchant in Glasgow, or by James Mitchelson Jeweller in Edinburgh.

The principal sources for the project are English and Scottish newspapers published between 1700 and 1780. The database covers all the regions of England and mainland Scotland.

Professor Simon Newman, of the university’s college of arts, said: “We do not have the words or sometimes even the names of bound or enslaved people who were brought to 18th century Britain. In many cases all that remains are the short newspaper advertisements written by masters who were eager to reclaim their valuable human property.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“These advertisements are important because they remind us that slavery was routine and unremarkable in Britain during the first three-quarters of the 18th century. This is made very clear by the placement of these newspaper notices offering enslaved people for sale or seeking the recapture and return of enslaved runaways. These advertisements appeared next to the mundane and every day news items and announcements that filled the pages of the burgeoning newspaper press.

“Slavery was not an institution restricted to the Caribbean, America or South Asia, and these short newspaper notices bring to life the enslaved individuals who lived, worked, and who attempted to escape into British society.

“This is an important resource for the understanding of slavery and telling the stories of the enslaved and slavery in Britain.”

Nelson Mundell, a research assistant on the project, said: “This project shows that it wasn’t an unusual thing to have slaves walking around the streets of villages, towns and cities the length and breadth of Britain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The adverts make for sobering reading as they describe scars and markings from whips or brands.

“It also shows that on occasion slaves wore collars or other manacles, sometimes with owner’s name engraved on them, as was the case with an 18-year-old fugitive called Ann who escaped from a house in Glasgow.”