Gerry Farrell: My guitar hero Vince had the year of his life

It’s hard to find any silver lining among the grey. But if you’ve ever lost a loved one to a terminal illness, you’ll know it’s not all gloom and doom.

Vince Woods was my children’s guitar teacher when I lived in Peebles. He was no ordinary tutor. He told his pupils only to bring him songs they loved. That way, he learned to play their kind of music. But he also encouraged his pupils to write their own songs. When they did, he recorded them, usually in his kitchen. Sometimes on these home recordings you can hear the cat meowing or the kettle boiling in the background. But those children left Vince’s house with a CD of their own composition, with Vince laying down drum, bass and keyboard tracks to make it as perfect as he could. He did all this for nothing. He wasn’t interested in money.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

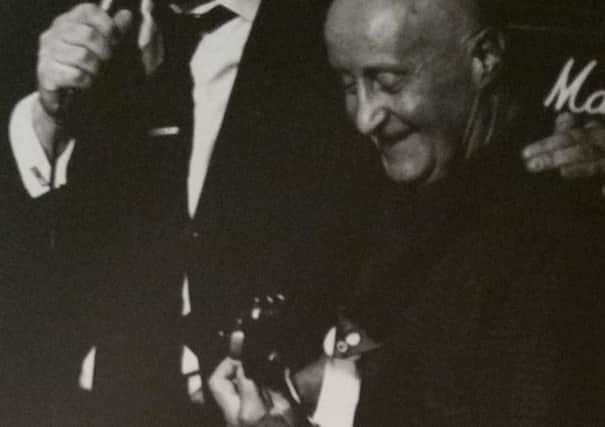

Hide AdI found myself writing songs, too, thanks to Vince. He would put a guitar track on a CD and pop it through my letterbox, telling me “write some words to this”. We made music for fun for a year. We got a band together and played a few gigs. One day, Vince stopped me in the High Street and asked me if I’d play a benefit concert to raise money for a friend who had breast cancer. I said of course but the lady died before we could hold the fundraiser. A week later I got a text from him. He’d been diagnosed with oesophagal cancer and given a year to live. Now the fundraiser was for Vince. We gave it the perfect name – Vince Woodstock. Nearly all of Vince’s pupils had their own bands by now and they were happy to play. It was some night. The kids brought the house down. Then Vince’s band, The Fatboy Band, came on to close the show. I have a black and white photo in the kitchen of me singing, with my arm round Vince’s shoulder. His head is bald thanks to the chemotherapy but he has a turnip-lantern grin on his face as he stands in front of a Marshall amp blasting out a blistering solo.

Vince told me later that it was the best night of his life. He also told me that his last year was the best year of his life. “I didn’t really do hugging until I got ill,” he said. “But now I get hugged every day.”

He was a shy man who had had a lot of mental health problems, but being face to face with his own death brought him out of his shell. Every morning he went for coffee with a group of female friends he called “my floozies”. At the start of his treatment he went for a ten-mile bike ride every day. He jumped out of a plane to raise money for cancer research. He met his hero, Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman. As he became weaker, his world shrank and it was enough for him to be driven round other people’s gardens to see if their herbaceous borders were better than his – he was a prize-winning fuschia-grower. He spent his last days surrounded by people who loved him. Every time I look up at that photo I remember his last year, the hard, ugly days dogged with pain and those other times when he felt more alive and happy than he ever had before.

I’m completely hooked on Neil and his talents

When I started out in advertising, I worked at Hall Advertising in Drumsheugh Gardens in the West End. It was more like a merchant bank than an ad agency, with deep-pile carpeting and oak-panelled rooms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe agency was 25 years old and the building was alive with legends. One of them was Edinburgh boy Neil Patterson. Neil wasn’t just an excellent copywriter, he was fishing daft. He used to come in early doors and gut trout in the studio sink. By the time I got hired he’d been head-hunted to a big London agency where he wrote brilliant ads for Land Rover. I scoured the awards annuals to find his work, memorised his headlines and tried to copy his style.

Years later I found an article about him in a fishing magazine. He’d been buying some flies in Farlows of Pall Mall when he felt a hand on his shoulder and a familiar voice said: “Hello, you’re my hero.”

It was Eric Clapton, pictured. Neil turned round, saw his face and said: “No, you’re my hero.” A mutual admiration fest between the world’s best guitarist and the world’s best flyfisher.

Neil’s life was transformed by a car crash. When he recovered, he converted a stable on the banks of the River Kennet. He sold his ad agency and began to travel the world, having fishing adventures from Alaska to Patagonia, all captured in his latest book, Flyfisher’s Chronicle. And then one day, quite out of the blue, I met him on the riverbank.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis clothes were the colour of the undergrowth. He said: “I’ve been watching you for an hour through my binoculars. You missed a rise.”

I hadn’t had a touch all day or seen a fish move but over the next three hours I watched the world’s best flyfisher turn into an excited little boy. “Look, there’s one, it’s feeding!” I couldn’t see a bloody thing. Neil cast his fly. “It had a go at mine, it’s trying again, got it!”

The water exploded as the Invisible Trout made a break for it. I learned more about spotting trout in those three hours than I’d learned in all the years I’ve fished. Once Storm Henry’s finished trashing the country, maybe I’ll plan another wee trip with my two-time hero.

Terry was all gold

One day, the late Terry Wogan was invited to 10 Downing Street by the-then prime minister, Maggie Thatcher. He was shown into a sumptuously appointed lounge. Moments later, in walked the Iron Lady herself. “Do help yourself to a drink, Mr Wogan” she purred, “it’s all on the taxpayer.” Terry looked at the drinks cabinet, generously stocked with whisky, brandy, gin and vermouth. “Is that so?” he said. “Then I’ll have water.”