Alexander McCall Smith: Too much modern art is bland, banal and forgettable

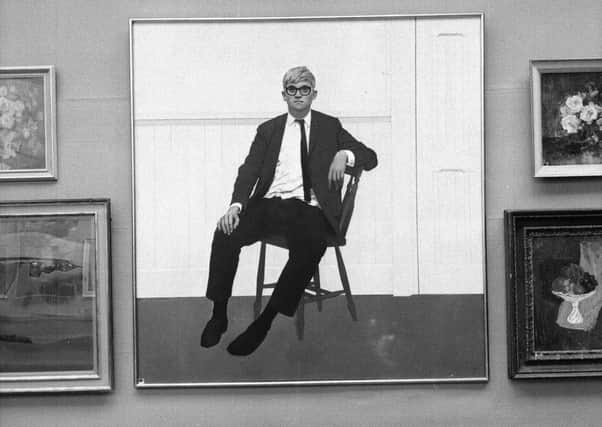

Earlier this summer I went with a friend to see the Edinburgh College of Art’s degree show. This is the show that is put on by graduating students, and is an opportunity for the public to see what art students have been up to. It has also traditionally been the time when the owners of galleries might call in to see if the next David Hockney might be lurking in the fresh crop of graduates.

The friend who accompanied me to the Edinburgh show is himself an artist, a graduate of a Scottish art college. His technique is painstaking and his art extremely sensitive. He takes a long time to finish a painting, and will worry about the tiniest detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI remember another Scottish painter, the much admired Jim Howie, who used to labour in a similar way on his gorgeous, luminescent abstracts, scraping off layer after layer of paint, to replace it, and then rework that new layer after a while. Gradually from this process there emerged paintings that glowed with light. His paintings haunt the walls they hang upon.

Elizabeth Blackadder studied here

So off we went to the Art College, that splendid building with its high windows intended to claim the northern light so beloved of artists. It is a building of rich artistic associations: here Robin Philipson was Principal; in these echoing studios artists such as Elizabeth Blackadder, William Gillies and Anne Redpath all learned how to paint.

It is now no longer an independent college, but has had the good fortune to become part of the University of Edinburgh, which has opened up a lot of possibilities for it.

I have been going to the degree shows for a long time, although I have hardly been to any in the last ten years. The reason for this was that they began to depress me. On the grounds that one should be prepared to reconsider things, I thought I might take a fresh look.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResisting the temptation to look at the intriguing displays of textile work, we went straight to the painting studios. There was some painting on display, but there was also a lot of conceptual work – installations of folded paper, old chairs etc.

That raises other issues, but on the painting to begin with... I looked at my artist friend. His disappointment was obvious. I wondered if he was asking himself whether painting was only acceptable; if it was being done ironically.

We moved from room to room. Nothing was said. In large part, the work on display failed to excite. There seemed to be a prevailing blandness about it and, what was particularly diappointing, not a great deal of evidence of skill in painting or drawing. Now, painting and drawing used to be the building blocks of artistic ability, and they were taught with rigour.

David Hockney is an example of how a thorough training in drawing makes a great artist. Of course, it seems that there has been a strong reaction against tradition, and art colleges do not emphasise these skills as they did in the past – hence the dissident schools that have been set up to make up for the lack of interest in the art colleges.

Art students seeking private help

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd that lack of interest is widespread: I know a highly regarded Scottish artist who told me he has had art students coming to him privately, asking him to teach them the skills that they were just not getting at college, where such things have been relegated or dropped. Nobody wants to downplay the efforts of our art colleges or the creative impulses of their students.

There are many talented students at the colleges who will be served by supportive artist tutors. The problem is that the situation seems to be somewhat unbalanced, with so little room being given to the traditional skills of painting and drawing.

Escape from the exhibition was achieved by dodging various installations – ropes and the like which might otherwise detain the visitor. Installation art has its possibilities, and it could be argued that all art is conceptual.

The problem is that much contemporary installation art occupies a very small – and often opaque – intellectual space, frequently fails to rise above the banal, and is often impenetrably personal. Such art will be forgotten, with the rare exception of the odd decaying shark, Marcel Duchamps’ pissoir that started it all, and perhaps the occasional unmade bed or pile of bricks. For the rest, it’s all been done.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStill, though, there are in our midst artists of significance – those who have something to say about the human predicament, those who expose us to beauty or profound emotion, those who make us look at the world with new eyes: they are still there, and their innate skill has asserted itself. The danger is that they will be condescended to, as is often the fate of those who question the prevailing artistic orthodoxy, which currently seems excessively focused on identity issues – on looking in rather than reaching out.

Painters survive in spite of the fact that all the glittering prizes are reserved for conceptual art. Could the art colleges not encourage – or enable – their students to be these people? Perhaps the answer is that which applies in so many other contexts: back to the drawing board.