5,000 Highlanders and an unprecedented exodus to Australia

The records from the Highland and Islands Emigration Society have been released online by the National Records of Scotland.

The society was set up in the aftermath of the Highland potato famine that put 200,000 people at the risk of starvation after the disease first hit crops in autumn 1846.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe society’s aim was to use emigration as the solution to the appalling destitution endured by many on the islands and west mainland coastal communities.

The society was funded by landowners, whose estates were increasingly becoming insolvent, and wealthy benefactors to support the passage of Highlanders to Australia.

In 1852, the society published a pamphlet calling for donations for the emigration scheme.

Prince Albert was listed as the patron with Queen Victoria personally donating £300 to the cause.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSupport also came from British colonies in Australia in return for emigrants arriving on their shores.

Residents from Skye were the first invited to apply for funding with around 3,000 people - many of them entire families - on a list of potential emigrants within a month of the scheme being launched in 1852.

Among those to leave were Donald Buchanan, his wife Ann and their three children, from Snizort on the island.

The emigration records include a note which described the Buchanans, who were given a promissory note for £14 ahead of the journey, as a ‘fine family’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe society replaced a system of poor relief that was seen by some over time to be too generous and ineffective at bringing around real improvement in quality of life on the Highlands and Islands.

Critics believed the system was at risk of making Highlanders effectively beggars and dependant on hand outs with moves taken to give a pound of meal only to those who had finished an eight-hour day of labour.

Sir Charles Trevelyan, assistant secretary to the Treasury and chairman of the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society, wrote to his aunt in 1852: “The only immediate remedy for the present state of things in Skye is emigration and the people will never emigrate while they are supported at home at other people’s expense...they will see the necessity of emigrating and working for their subsistence instead of living in Idleness and habitually imposing upon benevolent persons.”

The society, underpinned by Trevelyan’s conservative views and often blatant anti-Celtic bias, was determined to erase the “mistaken humanity” of charity and cure the social ills of the Highlands by removing its people, under coercive force if necessary, wrote Sir Tom Devine in his book To The Ends of The Earth, Scotland’s Global Diaspora.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Charles proposed that 30,000 to 40,000 people from the Western Highlands and Islands should emigrate, according to Sir Tom.

The chairman called for a ‘national effort’ to rid the land of ‘the surviving Irish and Scots Celts’ and encourage waves of Germans - ‘orderly, moral industrious and frugal’ - to take their place.

Newspapers of the day supported the emigration of Highlanders, including The Scotsman, The Glasgow Herald and The Inverness Courier.

Applicants for passage to Australia were chosen based on a person’s level of destitution and the skills they could contribute.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe society selected applicants and paid contributions towards assisted passage and clothing.

The remaining amount was met by landowners and public subscription with emigrants required to repay the Society all of the money given to them, so it could in turn be used to assist others.

According to National Records of Scotland, interest in the scheme increased.

In July 1852, 951 people were sent from the Highlands, all from the lands of Lord Macdonald of Waternish, and from the estates of Skeabost and Burnsdale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe emigrants were also later chosen from Harris, North Uist, Strathaird, Raasay, Iona, Adnamurchan and St Kilda. Emigrants from St Kilda travelled on board the Priscilla in October 1852.

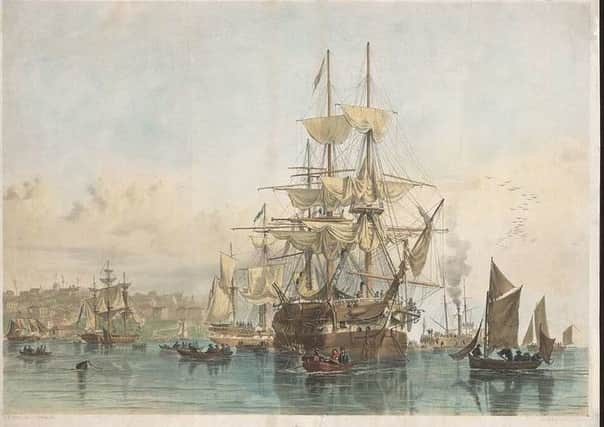

An article on the society’s published by National Records of Scotland said those boarding the ship Georgiana sang the 23rd Psalm amidst much sobbing.

However, it added: “Others, boarding a ship in 1852 were said to have ‘beaming countenances [that] would rather suggest the idea that they are anticipating the pleasures of a summer excursion then that they are tearing themselves away from their fatherland,” the article added.

The voyages were often beset with danger and disease. A mutiny was reported on the Georgiana, which left Glasgow for Port Philip in July 1852, after a number of passengers demanded to go on shore in search of gold.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, 100 people died at sea on the Ticonderoga, which left Liverpool in August 1852. Many hundreds were seriously ill by the time the ship reached Australia given outbreaks of scarlatina and typhus amid unsanitary conditions onboard.

The boat was banned from stopping at Port Philip and redirected to a deserted beach, now called Ticonderoga Bay, to be quarantined. Another 68 bodies were buried in the bay with reports many bodies were packed into mattresses and thrown overboard.

National Records of Scotland holds a letter received by John Macdonald in Scardoish, Moidart, from his brother who sailed on the Araminta in 1852.

While noting the “prettiest spot” of Colac in Victoria, he added: “The water is very bad and very scarce in some parts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is murder to bring old people out here; nothing will do but a strong family of men who can stand fatigue and keep sober.

“A man with a weak family had better stay at home, as he will not get an employer to support them for him; and suppose he did get £1 a day, he could not keep them in the town. The smallest room in town is charged 15 shillings weekly’.”

The society wound up in 1857 as economic conditions improved in Scotland and the demand for labour in Australia dwindled.

It was Trevelyan himself who arranged for the emigration records to be placed in Register House in Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, they serve as an accessible document that traces the lives of hundreds of Highlanders who left the toughest of circumstances behind in the hope of better days. While some did not survive the journey, for many it may well have been the voyage that saved their life.