Mickey Weir on playing Rangers, highs, lows and random acts of kindness

“Angels with Dirty Faces,” he chirrups, “fantastic film. Two wee toerags are rumbled by the cops. One runs away, realises he was dead lucky, and is good from that day onwards but Jimmy Cagney’s character is caught, punished and grows up to be a gangster.”

Weir prefers not to think he could have ended up trapped in a life of crime - “but 100 percent, it might have happened.” He accepts the cinematic analogy because as a teenager on one of Edinburgh’s toughest housing schemes, he got in with the wrong crowd. One night, before dribbling his way out of them became his speciality, he found himself in a tight spot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was a daft laddie but wised up in the nick of time,” says Weir, the wee winger who played such a big part in the winning of what was then called in the Skol Cup in 1991.

“The crew I was hanging around with in West Pilton got involved in break-ins. They didn’t do the actual stealing but would what we’d call set up houses for older boys. You kept shoatie and you could make yourself 20 quid, which was a fortune for scruffs like us.

“One time something went wrong. This house turned out to be occupied and the guy came racing outside and chased us down the Granton Ramps. Luckily I had my bike and I was able to get away.

“Sneaking home I was terrified of my dad finding out what I’d been doing. He never once lifted his hand to me but he always used to say: ‘Ye’ll no’ bring trouble into this house.’ That was a moment. If I’d taken the wrong path I could have ended up in more and more bother. It’s okay me saying I wasn’t cut out for that - and I wasn’t - but it could have been my fate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The street gangs were big at that time but fighting wasn’t for me either. Can you imagine? I’d have got battered every night. So I stopped all of that nonsense. I had to take a bit of bullying for opting out but that was a small price to pay. Otherwise things could have turned out a whole lot different for me.”

Instead things turned out just fine. He was an Easter Road idol, and just the way he played - deedle-dawdle, a winger from the trusty Scottish assembly-line of plucky, pint-sized patter-merchants - would have guaranteed that. But Weir further endeared for being a boy from the schemes, severely disadvantaged places which also presented the dangers of drugs, and who’d had to overcome being told he was too wee to ever make it in football.

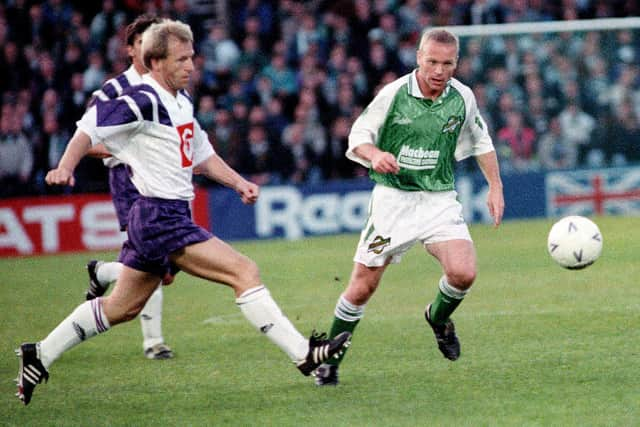

You know you’re getting old when you discover that Mickey Weir is 55. But, blued-eyed and smiley, he could still be the boy stuck out on the right wing during the 1980s and 1990s, his too-big shirt billowing in the breeze as he waited for John Collins or Paul Kane to dispatch him on a mazy run. Now working for Show Racism the Red Card, I thought he might have some good stories about Hibs-Rangers games and, when we meet in a Turkish coffee house in Leith, he does.

“I loved that fixture,” he says. “Rangers were a big team and Ibrox could be an intimidating place but I relished playing them. It was always a test but I always believed in myself. I was driven right from the very start. First day at Easter Road on my YTS contract I said to myself: ‘Right, if Hibs want rid of me they’re going to have to throw me out of here.’ If I failed it wasn’t going to be for the lack of effort.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“John and Kano were wee boys. too. On top of training the three of us went sprinting at Meadowbank every Wednesday night. I was brought up to have a good work ethic and where I was from toughened me up. We couldn’t afford much. When I was very young, one of five kids in a single-room house, those big boxes that were used to pack egg cartons were our beds. Christmas was a selection box, a tangerine and a wee toy. So was I going to muck up the chance to play for the Hibs? No way.

“Saying that about Rangers being big, they weren’t in my first games against them. First time at Ibrox we won in front of a dead small crowd [January 1985, 2-1 to Hibs, Brian Rice and Colin ‘Bomber’ Harris, att: 18,024]. Then a few months later we beat them again.”

Weir actually has two League Cup semi-final victories over the Gers to his name, Gordon Hunter being the only other Hibee to play in 1991 and before that in the two-legged encounter of the ’85-’86 season. The following campaign, though, brought a Rangers revolution, if not in the first instance a change of fortune against the Leith team.

“The Graeme Souness game,” he says of the Scotland great’s first-ever club match north of the border, an explosive affair which for him lasted just half an hour. “It was a glorious sunny day and before kickoff Rangers fans were running through Princes Street Gardens. There were so many of them, and maybe 7,000 locked out of the ground. I remember in the first few minutes the ball dropped from the sky and Graeme volleyed a pass out to the left wing. I was thinking: ‘Crikey, I’m in a game here.’ But Rangers thought it would be a stroll in the park and we got to Graeme. Billy Kirkwood niggled away at him and he took the bait. It still happens to this day that players come up here from England and get a shock when they find out that Scottish footballers, who may not be technically as good as them, are really fit and ready to battle.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe battles continued for Weir and in 1988 he was sent off at Ibrox, a game watched by his parents, Matthew and Mary. “It was a stupid tackle. The following day I went round to see my folks. ‘Hi Dad,’ I said, but he just blanked me. I went back a couple of days later and he still wouldn’t speak. Eventually he did. Read me the riot act. ‘Do that again in a game I’ll never come back to watch you play.’ Thing is, he used to say the exact same thing to me when I was ten years old.”

But in this often incendiary fixture Weir recalls, relatively speaking, random acts of kindness shown by the opposition. “Once at Ibrox I got into a shouting match with Walter Smith. He thought I’d taken a dive so I swore at him. After the game I couldn’t avoid coming face to face with him on the stairs and I apologised. ‘No son,’ he said, ‘it’s fine - you be yourself.’ Can you believe this: Bobby Russell coached me through a game: ‘Keep it simple, Mickey … Well done.’ And I laugh when I think of a reserve match against Rangers at the start of my career. Doddie [Alex MacDonald] rolled over and over despite me not touching him. On the ground he asked the ref: ‘Is he off yet?’ And soon I was - my first red card. I was seething but in the tearoom afterwards Doddie said: ‘No hard feelings, I knew I was going to nobble you today and here’s my advice: you need to calm right doon. Now we’re related: his boy is married to one of my cousins.”

I don’t suppose Weir was calm when Rangers beat Hibs 4-3 or 4-0. And what about the Christmas game from 1995 when the Gers seemed to go with a midfield of Scrooge, Herod and Gazza and won 7-0? “I don’t think I was playing that day.’ Sorry Mickey, the record books say you were. “Well, I’ve erased it from my mind!”

Spoken like a true Hibby. Weir grew up watching the Turnbull’s Tornadoes team with his father, grandfather and uncles. Dad was an HGV driver, Mum a cleaner. He says: “Money was aye tight so I’d get a lift-over. We never had much but then neither did the boy across the street or the lad down the road. When drugs flooded into the schemes it was unfortunately a way of making money when there were no jobs around. Boys who stole from houses would often give the proceeds to their mums. Folk did what they had to do to survive. But I had a good friend and others I knew killed by drugs.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt one point Weir’s chances of survival as a footballing prospect seemed non-existent. Told by a juvenile coach he was too small, he quit playing altogether. “I was devastated, heartbroken. I didn’t kick a ball for a couple of years. That was when the stupid stuff happened. I think my dad and grandad sensed something was wrong so they got me into pigeons. I became obsessed with them and spent all my time at the hut. And then they got me back into football.”

The family moved to Edinburgh’s Clermiston which to Weir “seemed like Hollywood” in comparison. Our man has only ever reached 5ft 4ins in height. While it was expensive growth hormone treatment for another little ’un, Lionel Messi, Weir tried to build himself up with his mum’s tripe. He laughs: “For ages I thought my name was Wee Man because that was all everyone called me.”

At 16 he left school. “Dad said: ‘I’ll give you a week to find a job.’ I went the length of Princes Street knocking on doors. At a hotel at the East End they said: ‘Can you clean dishes?’ ‘Aye,’ I said. I wasn’t going to be scared of graft. That was the working-class way.

“Fortunately I only had to do that for a few weeks. [Hibs manager] Paddy Stanton phoned the house to say he wanted to sign me. Dad couldn’t believe it. Paddy had been his hero as a player. Much later I found out there had been interest in me from some English clubs including Manchester City. But Dad never gave me the choice. I was joining the Hibs.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first team debut came at 17, away to Airdrie. “I was still cleaning the changing-rooms and sweeping the terraces. John Blackley [then a coach, later Hibs manager] caught me as I finished for the day: ‘Could you play left-back tonight?’” Once again there was an immediate and unequivocal “Aye”. “I had to rush home, ask to borrow my Dad’s suit and tie and meet the team bus at the Maybury roundabout.”

Little did Weir know that he would be back at the city limits eight years later to swap into an open-topper for the Skol Cup victory procession for Alex Miller’s team. He wasn’t much of a left-back but in his true position he proved to be a smash-hit. “The Hibs fans were wonderful to me,” he says, and endorsement offers duly arrived. “The funniest would have seen me running a pub. This businessman was going to re-name a bar in Lochend after me. ‘You’d have to pull a few pints,’ he said, ‘but there would be plenty of free bevvy for you.’ I had to tell him I didn’t drink.

“That goes back to the schemes when alcohol just seemed to lead to trouble with grown men fighting outside the pubs. I was terrified of it, developed this phobia and just decided: ‘Not for me.’ The only time I can honestly say that any has passed my lips was when my first son was born. What do you call it … champagne?”

But with the fame came hassles. His car - “A Vauxhall Belmont in cream, cost me a bit” - had paint thrown over it. He was headbutted in an uptown pub optimistically called Gatsby’s: “This guy said ‘Are you Mickey Weir of the Hibs?’ and then he did it, with his girlfriend right alongside him.” And the novelty of watching himself tussle with Rangers’ Derek Ferguson on a chip-shop TV showing Sportscene was quickly forgotten when he was chased down the street, fish supper in his hand. “I couldn’t take any more of that and when my contract was up and Luton Town said they were interested, I jumped.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProbably his size, if not his passion for his boyhood heroes, had made him a target. But you couldn’t keep Mickey Weir down, as Rangers were to discover in that semi-final 30 years ago. The move to the Hatters was short-lived and he was soon back in green and white, just in time for a triumph which he reckons was Hibs’ destiny after Wallace Mercer’s abortive takeover bid.

Cool as you like, Weir popped the ball onto the head of fellow player-turned-fan Keith Wright against the great rivals, and the pair combined again in the final against Dunfermline Athletic. “We had to win that cup because not long before guys like me were wondering: ‘Are we going to lose everything we’d been brought up with, everything we believed in?’” As the current team head for Hampden tomorrow they should be suitably inspired by the story of the little big man.

Message from the editor

Thank you for reading this article. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our sports coverage with a digital sports subscription.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.