The 'dark side' of Scots emigration hidden in asylum records

Professor Marjory Harper, professor of history at Aberdeen University, has studied links between migration and mental health and the reasons why Scots were admitted to asylums after leaving home for a better life.

Homesickness, alien environments, failed aspirations and even the impact of a long journey across the water have all figured in hospital records examined by Prof Harper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

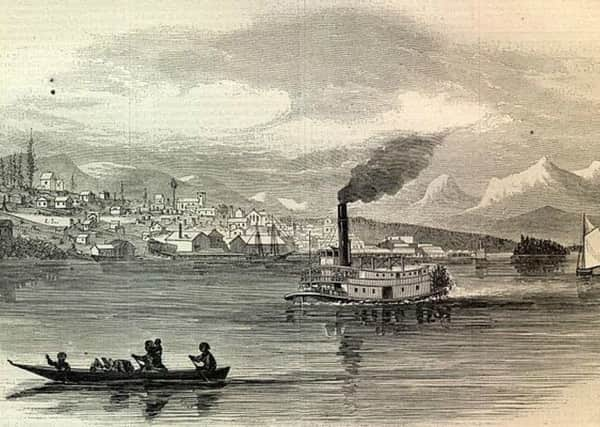

Hide AdHer research has focussed mainly on the old Provincial Asylum for the Insane, New Westminster, British Columbia, with records of some hospitals in Scotland, where a number of migrants ended up after returning home, also studied.

While success stories of Scots emigrants who flourished in politics and industry in their new homelands are routinely retold, the stories unearthed by Prof Harper portray a far bleaker picture of the realities of emigration faced by a handful of ordinary Scots.

Prof Harper said: “I think what the research shows is the dark side, the flip side of what we normally hear about emigration.

“Evidence preserved in the admission registers, warrants and case notes of patients admitted to the Provincial Asylum for the insane at New Westminster offers a sobering glimpse into migrant lives that were disrupted and dysfunctional, at the very opposite end of the spectrum from the fulfilling experience portrayed in recruitment propaganda.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecords relating to 1,200 patients at the hospital in British Columbia between 1872 and 1912 were studied by Prof Harper along with 340 individual sets of case notes with the academic having to seek permission from the British Columbia provincial courts to access the papers.

Those of British birth accounted for just over 20 per cent of the population of British Columbia during the period - but made up 36 per cent of asylum patients.

Scots accounted for 4.4 per cent of those living in BC at the time, but accounted for 7 per cent of patients at the hospital.

Prof Harper said the disproportionate number of migrants at the hospital could be expected given BC was a relatively new province, most of whose population had been born overseas or in other parts of Canada.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, a study of the conditions suffered by Scots patients show recurring triggers linked to migration.

Prof Harper said: “The whole process of leaving your friends and getting to your destination might be a trigger in itself.

One woman from Edinburgh who was admitted to the hospital in 1890 had fallen ill, according to her records, because of ‘indisposition and the long trip from Scotland to BC’. She had taken opium and attempted to commit suicide.

“Another trigger might be an alien environment. Think of a crofter and fisherman coming from somewhere like Lewis, close to the water and close to each other, who then found himself in the landlocked, mountainous interior of the province, hundreds of miles from the sea.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of the people who ended up in the Provincial Hospital were gold miners, Prof Harper said, with the unmet expectations of migration another factor that contributed to mental illness of settlers.

She said: “In British Columbia in the 1890s you had many men living up lonely creeks in the Yukon, hoping to make their fortune at the Klondike.”

“Homesickness was also a trigger, it was a big issue - the absence or breakdown of support network.”

Prof Harper referred to a letter found in the hospital archives from the sister of ‘C’ from Leith, who was admitted to the asylum in 1902 and died there 16 years later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe letter, written during the First World War, said: “It is very heart breaking, his constant desire to get home - where there is no home.

“If we could manage to pay his fare, would it be possible to get him transferred to any institution here, where we at least could see him? I would come out and see him, if I could.”

Records of Scottish asylums have also been checked as part of Prof Harper’s ongoing research into mental health and migration.

One record referred to a man called Charles, from Forres, who was first admitted to an asylum in Inverness in 1903 suffering from ‘acute mania and melancholia” and then transferred to Aberdeen and Elgin in 1907.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecords show he had previously emigrated to Colorado where he had worked as a cowboy.

An entry for Inverness District Asylum in 1866 details a man who had earlier worked as a gold miner in Ballarat, Australia.

Records list him as melancholic and delusional with the man claiming he was in possession of an entire gold field in Australia.

Prof Harper said she was interested in whether some migrants had a trait that made them “footloose and unrealistically ambitious.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe added: “Alot of people who ended up in hospital have been itinerant and of no fixed abode.”

Prof Harper will deliver at lecture at the University of Highlands and Islands in Inverness on Wednesday on her research.

She will also discuss her new book, Testimonies of Transitions, Voices from the Scottish Diaspora, which is due to be published in the New Year.

It follows interviews she has conducted with around 100 emigrants who left Scotland for overseas during the 20th Century

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing the publication of some of her findings in a book last year, Prof Harper was invited to Copenhagen to participate in a World Health Organisation meeting on migration and mental health.

She added: “They wanted a historical perspective - to use history as a foundation that policy makers can draw upon to inform current and future practice and policy. I find that very exciting.”