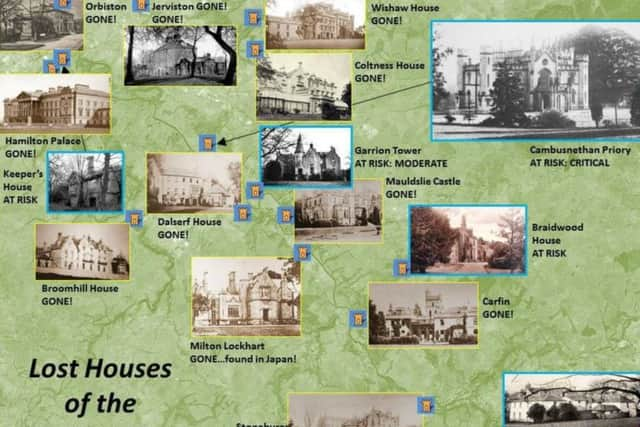

The great houses of the Clyde Valley that disappeared

The Clyde Valley was once the desirable home for gentry, industrialists and agriculturalists drawn to the plentiful lands of Lanarkshire.

But as fortunes faded, tastes changed and social change forced by the World Wars, many of the mansions which dominated this area simply vanished from the landscape.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome, like Hamilton Palace, once considered Scotland’s grandest country house, were demolished and others such as Cambusnethan Priory near Wishaw, a Grade A listed piece of Gothic Revival, cling on thanks to the work of volunteers.

Another, Milton Lockhart at Rosebank, was bought by a Japanese actor in the 1980s, dismantled piece by piece and transported east via the Siberian railroad.

Now, a little piece of Scotland stands as a tourist attraction and wedding venue in Unma-Ken.

Christine Wallace, who grew up in the Clyde Valley in the 70s and 80s and now lives in Germany, has become an impassioned researcher of the once-great houses of the area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe has set up the Lost House of Clyde Valley group on Facebook and organised the Friends of Cambusnethan Priory.

Ms Wallace said: “I grew up in the Clyde Valley opposite the ruins of an old gatehouse and these houses just fascinated me as a child and they continue to fascinate me.

“There is so much history in our land that we never really get taught and never hear about.”

Research by the group has so far has found that at least 11 mansions in the Clyde Valley have disappeared, five are at risk of collapse and one stands in a ruinous state.

In Upper Clydeside, another nine properties have gone.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe said: “Sometimes I get asked why you want to save these houses that were really for the elite and there are several answers to that.

“I don’t see them as only belonging to these families. A lot of the finance, the wealth, in these families and houses is down to the work of our ancestors, people like the miners, so in some way you feel that you have some ownership of it.

“And then you have to think of people like the stonemasons, the gardeners, those who made they houses what they were and kept them beautiful.”

World War One and the Great Depression were among the factors that brought the Clyde Valley hey day to an end for many of its wealthy residents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“These estates lost a lot of staff and money and the properties became a cost rather than an asset,” Ms Wallace added.

Meanwhile, the industry that had made the extreme wealth of some of the occupants was to prove to be their undoing.

Hamilton Palace was literally undermined by the coal seams that had been heavily plundered by its owner, the Duke of Hamilton, who held the mineral rights across most of Lanarkshire.

It had also been let out by the 13th Duke as a naval hospital during World War One.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnce peace was declared, he had little appetite to return to the sprawling pile. The price of building materials required to bring properties back to good order had also soared.

Hamilton Palace was eventually demolished in 1925 with its vast collection of art and antiques sold for today’s equivalent of £24million.

The entire Great Dining Room was reconstructed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

The mausoleum of Hamilton Palace still stands off the M74 to the west of Strathclyde Conntry Park and is opened up one day a year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We have this important remnant of the estate but not everyone knows that there was also a great big palace here too,” Ms Wallace added.

Follow the River Clyde south east for around 12 miles and you will find the site of the former Mauldslie Castle, built by revered architect Robert Adam, in 1792. Now demolished, a sewage works can be found instead.

Maudslie was built for the 5th Earl of Hyndford and secured by Mr James Hozier, former MP for South Lanark from 1886 to 1906. It is said on election night victories, people would make a beeline for the castle to wish him well. It was passed down through the family but demolished in 1935. The elegant gatehouse does, however, survive.

Over the Clyde to the east sits Cambusnethan Priory near Wishaw, built for the Lockhart of Castlehill family in 1819. The gardens were noted in the New Statistical Account for their beauty, but they just don’t exist anymore. The house is “close to the brink,” Ms Wallace said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDescribed as one of the last great houses of the Clyde Valley, the A-listed building was bought in the 1960s and partly turned into a restaurant where medieval banquets were held. It fell into ruin in 1984 and later used for music video shoots.

“It is a place that gets into people’s imaginations,” Ms Wallace said

Plans by its current owner to convert the building into to flats have been systematically blocked with the Friends of Cambusnethan Priory working to keep the site clear of vegetation as a new use is found for the site.

There are also “Clyde Valley survivors,” Ms Wallace said, such as Corehouse, near Lanark, a prime example of mock Tudor in Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was built in 1824 by Edward Blore, who went on to complete Buckingham Palace, for Lord Corehouse, a former Dean of the Faculty of Advocates.

Corehouse was built near the falls of Corra Linn as his country retreat and remains within the family.