Scotland's last 'penguin' killed amid fears it was a witch

The visits of the “stateliest” of all the sea birds, with its long curved bill and white eye patch, would be retold down the generations.

But despite its celebrated status on the archipelago, it was here that the last Great Auk in British waters was killed to extinction in 1840.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was stoned to death by a group of fisherman petrified that the three-feet tall bird was actually a storm-conjuring witch.

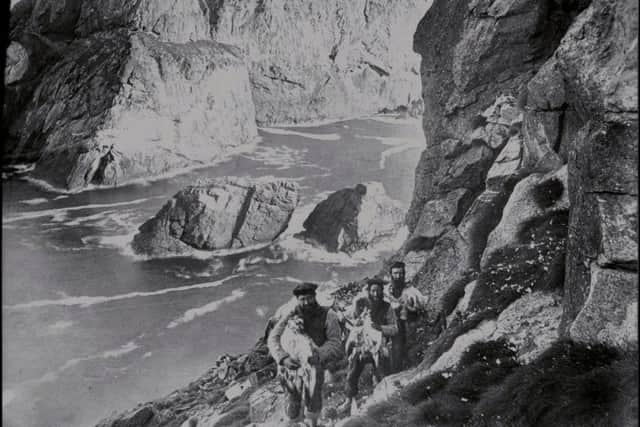

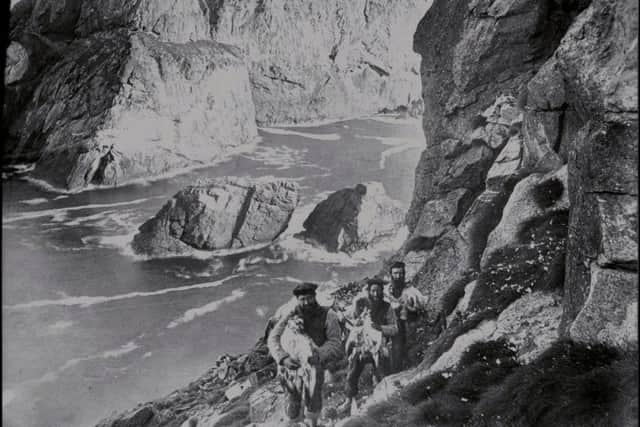

They discovered the last Great Auk on a fowling raid to the sea stack Stac-an-Armin.

“Prophet-like that lone one stood,” one of the men later said of the encounter.

Errol Fuller, author of the Great Auk, The Extinction of the Original Penguin, described the last hunt.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Here lying asleep on the ledge, they found - and caught - a large, plump bird of a kind they had never seen before. But they knew immediately what it was,” Fuller wrote.

He added: “They took the bird to their bothy and kept it confined for three days while they decided what to do with it.

“Sometime during these three days a storm blew up, and the men, unable to get back to their home island, were forced to sit out the storm in the bothy with their strange companion.”

The men, at some point, got frightened in their isolation with the group slowly becoming clouded by the superstitions held close by the islanders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The idea crossed their minds that they bird wasn’t actually what they thought it to be. Perhaps it was a witch, they reasoned, and perhaps it was a witch with the power to raise storms,” Fuller said.

Amid worsening weather and increasing agitation of the men, the bird was killed in the bothy although other accounts have suggested the bird was taken to the men’s boat.

The bird was reportedly beaten to death with two stones in the confines of the bothy for more than an hour, according to accounts, with the remains of the bird left behind as the mean headed for home.

It was the end of the Great Auk in the British Isles.

Just four years later, the last Great Auks in the world were killed off Iceland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1697, Martin Martin’s A Late Voyage to St Kilda described the Great Auk, or the Gair Fowl, as the “stateliest” of all the sea birds.

An 18th Century account described the bird as the “most remarkable” fowl of the island for its “enormous size” and rarity who laid their eggs a little above the sea mark on rocks of easy access.

It described how the birds were killed by “surprising them where they sleep, or by intercepting their way to the sea and knocking them on the head with a staff.”

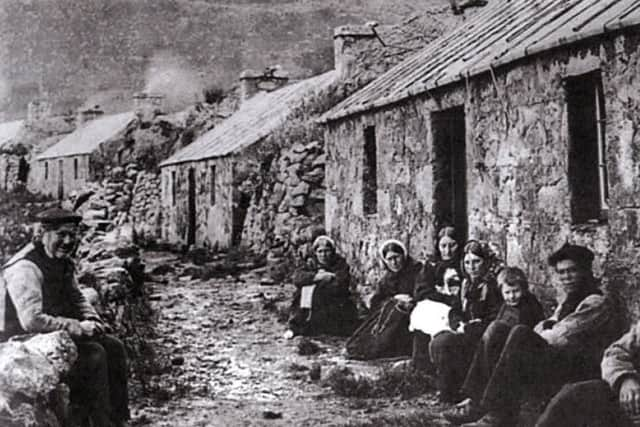

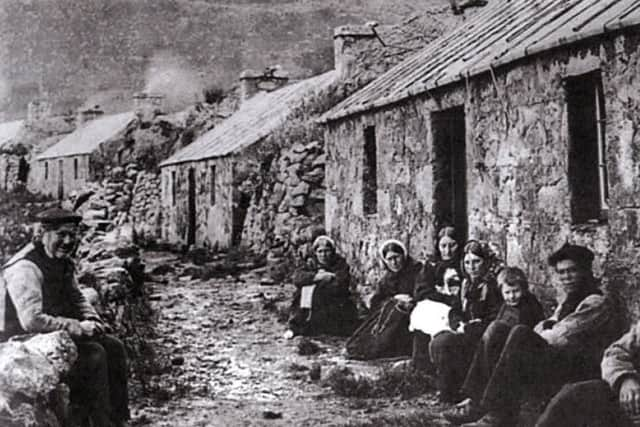

Sea birds were the main food source for St Kildans, who rarely fished due to the hazardous waters that surrounded them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA census from 1764, found just last year, details how each of the residents of Hirta, the main island, ate 18 birds a day and 36 wild foul eggs.

In 1876, nearly 90,000 puffins were said to have been taken for their meat and feathers with men abseilling down cliff faces to fetch gannets and fulmars. Skins were used a shoes and the oil became a valuable source of income.

Great Auks were also easy pickings for humans seeking a meal, according to the RSPB.

Another 18th Century account details how the seabird eggs were of an “astringent quality” with the birds preserved in stone huts, or cleits, and dried in the cool air.