100 Scots reveal why they left their home country behind

The testimonies were gathered by Professor Marjory Harper, of Aberdeen University, who has long researched migration and the Scottish diaspora.

She travelled to Australia, Canada and New Zealand for the project with excerpts of the accounts now published in her new book, Testimonies of Transition, which explores why people were compelled to leave their home country behind.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Harper said: “Emigration and diaspora are about people and no two people are the same. Every single person has a different story to tell but of course there are recurring themes.

“The main objective of everyone who left Scotland was a search for betterment. That even could come down to the betterment of the weather, which came up very often. A lot of people mentioned the greyness of Scotland.

“There is no one mould into which the emigrants can be fitted. The research has reinforced the diversity of those who left, the complexity of the decision-making, and the multi-faceted nature of the whole experience.”

Between 1951 and 1981, 753,000 people migrated from Scotland with 45 per cent moving to England and the rest heading overseas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

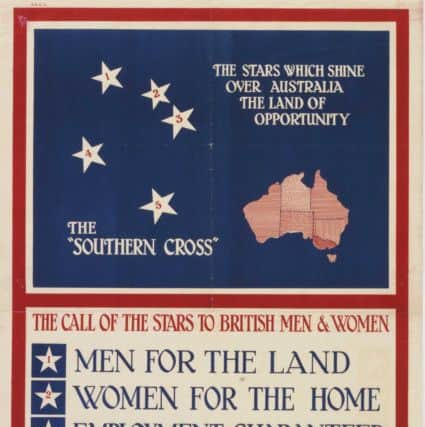

Hide AdThe £10 passage programme operated by the governments of Australia and New Zealand between the mid 1940s and early 1970s represented a key phase of migration, Prof Harper said.

She added: “Some who left Scotland were following a family tradition, sometimes there would be a tradition of wanderlust in their families.

“In some cases it was parents looking for a better education for their children and housing was also a factor. One emigrant in Dunedin recalled that her father had taken the family to New Zealand in 1953 partly because he wanted his daughter to have a better education, and partly because he was frustrated at the local council’s refusal to give him a bigger council house.

“Some people wanted access to a better job market. Others wanted to pursue adventure – that was a big factor for many who took up the £10 passage offer.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe effectiveness of the subsidised migration schemes of the mid 20th Century caused alarm for politicians, including nationalists of the day.

Douglas Henderson, who later became Deputy Leader of the SNP, petitioned the Prime Minister of New Zealand to withdraw his country’s emigration agents from Scotland.

Henderson claimed that the benefits gained by New Zealand came at the cost of a ‘disastrous drain of many of the finest and best of Scotland’s youth’.

In a letter to the New Zealand Premier, Henderson went on to accuse the Westminster government of ‘actively and deliberately fostering a large-scale clearance” of an “under-populated” nation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Harper interviewed two former recruitment agents, Bob Smart and Gordon Ashley, who worked for Ontario and Australia. She also included an earlier account of Hec Macmillan, an Australian recruitment agent in Scotland in the 1950s.

Mr McMillan recalled the impaction of nationalist opposition to the migration schemes after being sent to open a new office in Edinburgh in 1959.

Mr McMillan recalled a call from the police to inform him of “highly abusive slogans” painted on the front steps of the office.

Meanwhile, a ‘bundle of immigration literature’ was put in a ‘wee pile’ and set fire to in St Andrew’s Square while protestors danced an eightsome reel around the burning paper, according to the accounts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe group Scottish Patriots are known to have embarked on such protests.

Mr McMillan also gave insight into his day to day work of assessing suitable candidates for the migration scheme.

He believed Glasgow would have been more a more fruitful recruitment field than Edinburgh, particularly given the concentration of skilled shipbuilders in the area which were in high demand by Australia.

Mr McMillan said: “The Glaswegians tended to be very earthy, tied to the Clyde... and it was from there that we got the bulk of the skills which were in very, very short supply in Australia back in those times. We used to absolutely welcome these skilled workers with open arms.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe also recalled the interview of a family of seven who lived in one room and a kitchen. The father, who was unemployed, was a ‘beat up little fellow’ with his wife described as a ‘tired looking woman’

The only time the woman spoke was to say she could sell her engagement ring and other bits of jewellery to get spending money for the boat to Australia.

McMillan ignored the Department’s guidelines and recommended the family for acceptance. He later heard from a colleague that the family had moved into a four-bedroom house at the Williamstown Migrant Hostel in Melbourne to replace the caretaker.

In Testimonies of Transition, Prof Harper also compares the experiences of those leaving Scotland in the 20th Century to those who departed during the 18th and 19th Centuries, when Highland Clearances and deprivation were among factors at work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne interviewee, Joan Noble, originally from Lewis but who later settled in Aberdeen, moved to Vancouver Island with her husband and two sons in the 1980s.

She spoke of the historical narrative of migration from Scotland and referred to the “literature of exile - sad songs, sad poems, the anguish of exile, and the sorrow and so on.”

Mrs Noble added: “Well, that’s how it used to be, ’cos (sic) it was not by choice that they came in the past.

“But we came by choice, and it’s been nothing but good things. We came not because we needed to – John was deputy of a school in Aberdeen, and we had a lovely life in Aberdeen, but, I don’t know, there was some kind of restlessness in the air in the ’60s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And the weather had become absolutely abysmal. We could never get a nice summer, my children were never outside playing the way I wanted them to be. I had to put them into sou’ westers and little wellies and all that, you know.”

Prof Harper said it was impossible to quantify whether migration from Scotland had been a success for those who left, given the scope of her research.

But Prof Harper said the overwhelming experience of those she spoke to was a positive one, apart from one particular case.

She added: “There was one woman who returned to Scotland from overseas and she bitterly regretted leaving, even four decades on.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf Harper is now looking for more Scots who have emigrated to contribute their story to an enhanced talking version of the book. She is particularly keen to speak to those who relocated to the Indian sub-continent.

The recordings of interviewees will be digitised and archived at Aberdeen University library.

-Testimonies of Transition is published now by Luath Press.