Armistice 100: What was life in Edinburgh like during World War One?

and live on Freeview channel 276

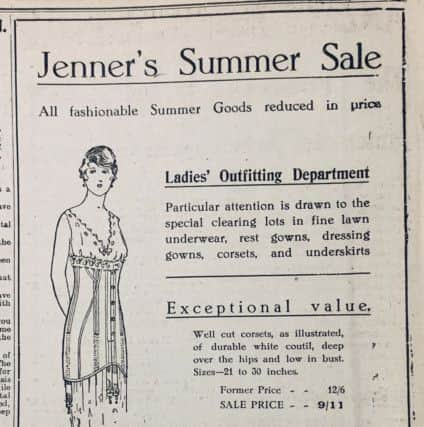

A life where a ten-pack of Players Navy Cut cigarettes would have set smokers back 5½D; where “remnants and oddments” could be secured at “merely nominal prices” in the Jenners sale; and where adverts for servants across the Capital were commonplace.

But it was a life ravaged by war with the devastating realities of the 1914-1918 battle felt on almost every page.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Edinburgh Evening News archives are an engrossing read at the best of times, but the 1918 volume is perhaps especially so.

Life carries on as normal in so many respects – cinema listings, job adverts, court reports – yet the horrifying impact The First World War has on the city is felt loud and clear.

Nowhere is this better seen than on the announcements page where, in one column, a proud mother tells of the birth of her baby boy – yet in another a grieving mother details the death of one more of her sons “killed in action” and “deeply mourned”.

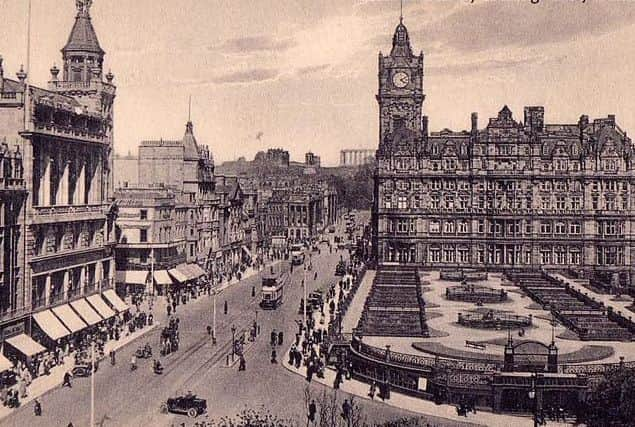

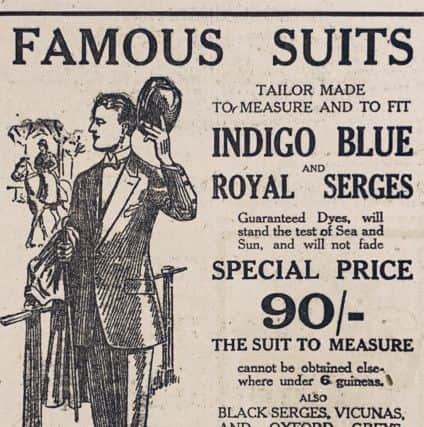

For those at home, Edinburgh was a vibrant city brimming with entertainment, shops and businesses. Adverts in the 1918 editions of the Evening News feature many now familiar names – Jenners, H Samuel, Lipton’s tea – alongside once long-standing Edinburgh family firms and brands which have since bitten the dust, such as B Hyam tailors, at 124 High Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey include an advert for Retep scalp oil, sold by a Madame Tensfeldt from a “private flat” at 137 Princes Street.

“Why lose your hair when it can easily be forced to grow luxuriantly,” the advert in August of that year reads, “simply by feeding it with Retep oil. This most wonderful discovery of science gives proper nourishment to the hair roots. Price 2/9.”

There are regular adverts for Cockburn’s Pills which guarantee help for readers suffering from “habitual constipation”, as well as entries for Scott’s Emulsion, which says it will treat “all lung troubles”.

One hundred years ago the Evening News filled its entire front page with adverts, as well as listings for the seemingly endless number of cinemas across the city, including the Tron Picture House on the High Street, the Palladium on Fountainbridge, and the Garrick Theatre on Grove Street - all long gone by 2018.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were also lengthy “wanted” columns including entries for jobs, accommodation and everyday household items such as furniture.

“Girls wanted for machine room,” one advert reads. “McDowell and Sons, Torphichen Street.”

Another requests an “experienced servant” to work at a property in Colinton housing a family-of-three, with an annual wage of £26-£30.

But yet again, the reality of war is never far away.

“Urgently wanted for munition purposes,” one advert states. “Every kind of old books and waste paper, brass, lead and other non-ferrous metals of every description. Highest prices paid, bags supplied free. E Chalmers and Company Ltd, Bonnington, Leith.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuch adverts stand alongside the daily Roll of Honour, listing the fallen soldiers from across Edinburgh and its surrounding district, making for a harrowing read.

Few could fail to be moved by such entries: “Private T McGuire, Royal Scots, was killed in action on 23rd August. His widow resides at 100 Pleasance.”

Similarly, “Corpl. William Macpherson, 24, Royal Scots, was killed in action on the 23rd August. He was the second son of the late Mr C W Macpherson and Mrs Macpherson, 10 Moncrieff Terrace. He joined in November 1914 and was wounded in April 1917. Before the war he was employed with Mr White, plumber, St Andrew Street.”

For many however, life operated much as it did before the war, with busy courts of law dealing with everyday crimes from 1918 – including a notorious pickpocket who was sentenced that autumn to 17 years in jail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA report from the High Court told of a Thomas Gilmour who appeared on “charges of theft and of being an habitual criminal”, who in an “Edinburgh public house” stole £20 from a mining contractor; £32 10s from a private in the Black Watch while in Dundee; a purse containing 9s 6d from a plumber on Waverley Bridge; and £11 from a farmer on a Portobello tramcar, to name but a few.

Lord Skerrington is reported to have said that Gilmour seemed to have “applied himself to a deliberate course of dishonesty” before sending him down.

Similarly, four members of the crew of the steamship Borg, while lying at the Albert Dock in Leith, were fined in court for smuggling.

A report from the Midlothian JP Court read that one of the men “was fined £6 and expenses for attempting to export half a pound of tobacco, two woollen shirts and a woollen jersey” after complaints had been lodged with the chief preventive officer of customs at Leith.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurther along the road in 1918, the Evening News reported on the demolition of the 1250ft Portobello Pier which had been built in 1871 for a staggering £10,000. Although an initial success, the pier became expensive to repair and was no longer used for “passenger traffic” as “the war put a stop locally to such pleasure trips”. A decision had been made by its owner, Mr M P Galloway, to take the structure down by September 1918.

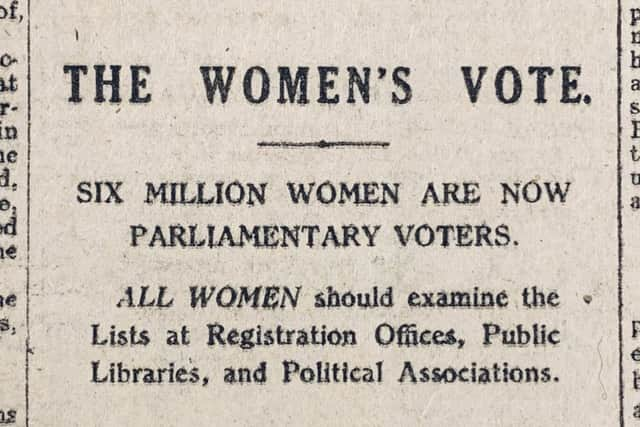

Alongside daily adverts for National War Bonds and notices urging emancipated women to “examine the lists at public libraries” to see if they are one of the six million females who are now “parliamentary voters”, is a small article in the autumn of 1918 which hammers home the reality of war for many families across the Capital.

“Gunner Robert Alison RFA, ward 7, Edinburgh War Hospital, Bangour,” it reads, “appeals on behalf of the wounded Tommies in his ward for the use of a gramophone, to help to pass long hours of the winter nights. The soldiers give a guarantee that the instrument would have every attention and care.”

Thousands of Edinburgh men went to war and thousands did not come back.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor many of those who did, their time on the battlefields would have transformed them physically and mentally – and the struggle they faced as they tried to find their place in post-war Edinburgh can never be underestimated.