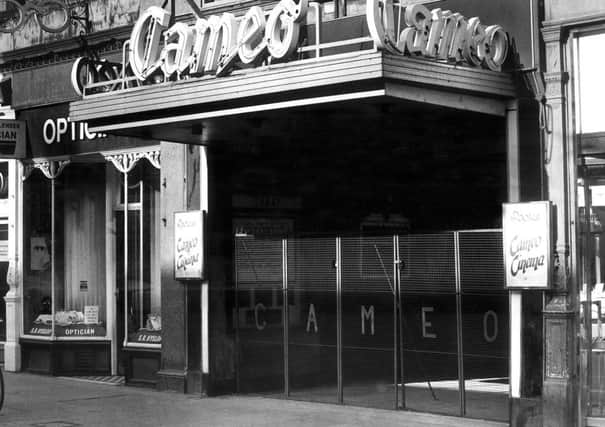

Cameo cinema celebrates 100th birthday

When the doors opened to a picture house in Home Street 100 years ago tomorrow, the curtain went up on a world of romance and high drama, one in which film fans could be scared out of their seats, quietly weep or laugh uproariously as the magic of moving pictures took them to places they could barely have dreamed of.

Then known as the King’s, it would be reborn as the Cameo. And apart from that name change and a few vital modern touches – including today’s three dimensional screen showing images which no doubt would have left the pre-First World War audiences bewildered – not much has really changed since those early film fans settled down beneath the ornate plaster ceiling for a couple of hours of escapism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Tollcross cinema, one of the oldest picture houses still operating in Scotland, will celebrate its centenary tomorrow when invited guests will gather to watch a special preview screening of Inside Llewyn Davis, a Coen brothers’ film about a New York folk singer starring, among others, Carey Mulligan and Justin Timberlake.

The birthday party film casts a backward glance to the folk music movement of the early Sixties. Yet back in the real world, by that same Swingin’ Sixties era the Tollcross picture house had already well and truly staked her place in the hearts of city film-goers for half a century.

Only a short blip in the Eighties, when modern technology in the form of home videos plunged many cinemas into darkness, and a post-war spell in the Forties have interrupted screenings.

Among the Cameo’s most avid fans is Genni Poole, whose father, Jim, took over the King’s in 1947, and reopened it as the Cameo. He stressed its arthouse credentials in an advert which appeared in the Scotsman in March 1949, announcing it as “A cinema for the discerning” showing “week by week carefully chosen films of artistic merit screened in an atmosphere that sets a new standard in cinema decoration and comfort”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a pledge which, according to Genni – who grew up playing in the empty cinema while her dad organised behind-the-scenes business – is just as relevant today.

“The Cameo is not just a box where people go and watch a movie and get all the special effects but could be sitting in any place in the country,” she says.

“The Cameo is actually a cinema with a beating heart. It’s an experience to go and watch the film in the Cameo.

“In the Cameo you know you are in a historic building and in a special, unique place. I look on her as a very grand old lady.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoving pictures were first screened at the venue on January 8, 1914, when film-goers arrived to find 673 seats, a revolutionary mirrored screen – the first of its kind in the country – and a live orchestra in place to provide the musical accompaniment to the silent films.

Many would already have witnessed the birth of moving pictures brought to them by Genni’s grandfather, John Poole, who with his family ran dioramas – mobile theatres showing often historically themed pictures with images which changed depending on how they were lit.

By the time her father took over the then King’s in 1947, the Poole family was running the Roxy in Gorgie, the Synod Hall and other cinemas across the country.

Running the cinema was a dream conceived by Jim in the maelstrom of the Middle East where he served during the Second World War with a remit as chief entertainment officer for the troops.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He put on film shows and had to source the movies from wherever he could,” Genni explains. “He showed many foreign films, many of which had not just one lot of subtitles but many subtitles in different languages. He gained a huge amount of experience and love for foreign films and he brought that back to Edinburgh.”

He returned to find the King’s in disrepair as the impact of war and rationing took its toll on leisurely follies like the cinema – and an opportunity to share his love of foreign and art movies.

Once in charge he opted not to rip out her ornate interior for something more practical and instead spent the next two years battling to restore the remarkable interior to glory.

“My father would tell stories about how the water dripped through the roof and they had to place jam jars at strategic places,” says Genni with a laugh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And when they first moved in there were lots of strange noises which turned out to be rats. There were structural problems too, but he upgraded everything and ended up with something to be proud of.”

Restoring the picture house was just part of Jim Poole’s dream – the other was to introduce the films he loved to a post-war audience who might prefer glossy escapism and sugar-coated romance to the gritty and challenging world of art movies.

“My grandfather was quite doubting,” adds Genni. “He thought that was risky programming but said if he wanted to do it, then go ahead but you’re crazy.”

It turned out to be a masterstroke, for the revamped Cameo brought fascinated audiences a taste of a certain style of film – and glamour – they’d otherwise probably never see.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor its opening night the new owner had secured the right to premiere a brand new French subtitled movie, La Symphonie Pastorale. It told the story of forbidden love of a pastor for a young blind girl – weeks before it would go to Cannes to win the equivalent of the Palm D’Or.

“At first people were bemused and came out of curiosity. Then they got hooked and realised a whole world had opened up to them,” says Genni, who now lives in Berwick-upon-Tweed.

“It was a way to see different cities and cultures, stories and pictures which were completely different to what they were used to.”

Meanwhile Jim Poole’s eye for marketing kept the cinema in the public gaze by bringing huge name stars to the venue for lectures and personal appearances, among them Orson Welles and Cary Grant, while Sean Connery was enlisted to open its cinema bar in 1963.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At one point people would queue around the block, but then it became difficult being an independent cinema,” adds Genni. “My father had to compete against the new multiple screen cinemas and then video which made a dent in every cinema business.

“When people started to watch films at home it was very strong competition. But the Cameo has a good following among people who have a great affection for cinema.”

Her father retired in the early Eighties and with no takers interested in continuing the business, the Cameo’s lights temporarily dimmed. By 1986, it was up and running again as part of a small independent chain.

Moves to turn it into a superpub were seen off in 2005 by a strong outpouring of support and affection from locals and celebrities. Projectionist Eric Saunders, 57, who has worked at the Cameo since 1987, says the business and the people behind the scene has had to evolve. In the early days of the King’s, training a projectionist could take years, now it can be done in hours.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Today the projectionist role is very much about sitting in front of a computer monitor, there’s very little ‘hands on film’ any longer. The film arrives on a hard drive, it’s downloaded to the system and it’s a case of pushing buttons in the right ways.

“Forget any notion of it being like Cinema Paradiso,” he says.

He’s not a huge fan of the modern, big-money blockbuster movies either, preferring the days when the Cameo showed 35mm film – even if it meant being constantly on your toes in case anything went wrong – and the images on screen had a softer quality, in more ways than just one.

“I think there’s a romance to the old 35mm images, both in digital and modern factors. In modern day life, we’re getting away from any subtlety, everything is a lot more harsh and fast moving.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGenni agrees the old days were the best. “As a child I thought it was a magical place. The satin curtains and the red velvet seats . . . . it was just very special. It is a very precious cinema in terms of where it is in people’s hearts and its individual character. We have got to hold on to it as much as we can.”

Always a bright light in our city arts heritage

THE King’s Cinema opened in 1914, taking its name from the nearby King’s Theatre. It was bought by Jim Poole in 1947, renovated and reopened in 1949 as the Cameo, specialising in art and foreign movies.

It closed temporarily in the early Eighties after Mr Poole retired, but reopened in 1986 under ownership of a small chain of cinemas which retained its arthouse theme. It is now owned by PictureHouse Cinemas, part of Cineworld.

Movie A-lister Quentin Tarantino declared the Cameo among his favourite film houses when Pulp Fiction was shown there in 1994. And the cinema hosted the 1996 premiere of Edinburgh’s best known cinematic offering, Trainspotting. The venue has played host to stars from Lillian Gish to Charlize Theron, Patsy Kensit to Danny Boyle, Ewan McGregor and Michael Redgrave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt has even starred in films itself, featuring in Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist and in Women Talking Dirty, starring Helena Bonham Carter.

The Cameo’s future looked bleak in 2005 when its owners moved to close it down and reopen as a “superpub”. However, support from locals and celebrities – including Karolyn Grimes, who as a child starred in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, Ken Loach and Ewen Bremner – forced an about-turn. Recently, its long links with the Edinburgh Film Festival were severed because its modern screen was deemed unsuitable.