The shocking 1920s Edinburgh colour bar that discriminated against ethnic minorities

and live on Freeview channel 276

Dr Clare Torney, Head of Analytics, Reporting & Audit at Historic Environment Scotland, has uncovered shocking details of the Edinburgh colour bar that was adopted by numerous venues across the city a century ago.

At its peak in the inter-war period, the highly-controversial bar policy saw a variety of different establishments, including restaurants, cafes, clubs and hotels, forbid people of colour from entry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the late 1920s, the Edinburgh Indian Association and the Indian Students’ Union began to receive letters from local venues to inform them their members were no longer welcome.

One such letter was published in the Guardian newspaper. It read: “I should like you to inform all members of the Union who use the above restaurant, on and after Saturday 23rd inst. admittance will be refused.

"I may add that this is not directed against the Indian community only, but includes all coloured patrons.”

Popular dance halls, such as the Edinburgh Palais in Fountainbridge, which would regularly welcome up to 900 dancers on busy evenings, began to pursue a strict door policy based on the colour of people’s skin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe many Asian, African and Caribbean residents that made up Edinburgh’s ethnic community of the era were prohibited from joining native white Scots on the dance floor and were effectively treated as second class citizens in their adopted country.

Dr Torney tells the story of a 17-year-old Punjabi student, Diwan Pitamber Nath, who witnessed the appalling shift in the city’s attitude towards people of colour first hand.

In 1927, Mr Nath joined the Edinburgh Indian Association in condemning the racist policies being pursued by certain businesses.

The young student wrote to The Scotsman explaining how this would cause great resentment among his compatriots in India, where the people were growing increasingly fed up at being ruled by the British and were calling for independence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote: “These students … would naturally tell their countrymen what they had undergone. The bar … would become known to, and would be resented by the millions in India.”

In a separate letter to The Scotsman dated August 8 1934, a person of Indian origin describes the horrifying ordeal of trying to find a hotel that would accommodate their countryman, an alumnus of Edinburgh University. A dozen hotels were approached, each one refusing the Indian national a room for the night.

The anonymous individual wrote: “At one popular hotel in the south of the city, I was definitely and honestly (of course in apologising tone) told that the proprietress cannot admit any coloured person in the house.”

Dr Torney also reveals that one prominent Edinburgh hotel even refused entry to a visiting African American bishop as late as 1937.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

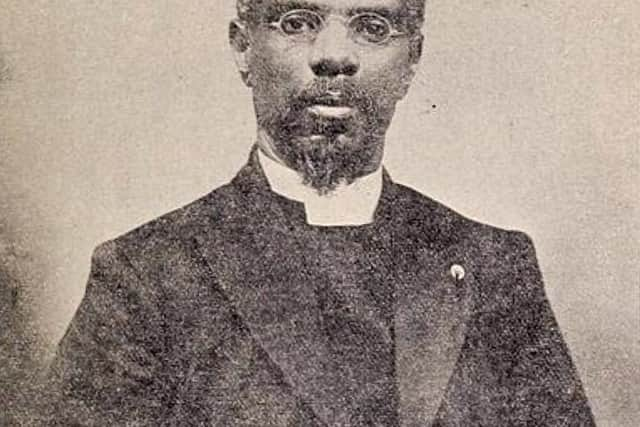

Hide AdBishop William Henry Heard, who had been brought up in the state of Georgia a slave, before being liberated in the American Civil War, arrived in the Scottish capital presumably in the hope that he would be spared the racial injustices that were all too common to him in his homeland. The civility of Edinburgh, sadly, proved to be only marginally better than the confederacy of his youth.

The bishop arrived with his niece at the prestigious North British Railway Station Hotel – now the Balmoral – and was told to look elsewhere. After fours of searching, the bishop eventually secured a room at a smaller hotel in the West End.

The incident sparked a great deal of fury among locals, many of whom expressed their embarrassment at the bishop’s treatment.

Quizzed by the press, some hotel managers refuted the suggestion that they had adopted a colour bar, instead claiming they had sought to avoid provoking the “tremendous antipathy” of their white American guests towards people of colour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the colour bar gradually vanished, it would take another 40 years and the passing of the 1976 Race Relations Act to put such injustices to bed once and for all – or so was the intention.

There are many people of colour currently living in Edinburgh who will attest that our society still has some distance to go to fully eradicate the prejudices of the past.

Human rights activist and emeritus professor at Edinburgh's Heriot-Watt University, Sir Geoff Palmer, says he continues to experience racial prejudice to this day, albeit in far more subtle forms than the colour bar of the 1920s.

Sir Geoff, who was recently appointed by Edinburgh Council to lead a new slavery and colonialism review group, said: “I was invited to speak at an institution in Edinburgh just last year. The guy at the door asked who I was and if I knew anybody. I said I knew the former boss and he asked if I had been his chauffeur.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In my view it is clear that we haven’t yet got rid of those historic prejudices. The colour bar of the 1920s was based upon a lop-sided education that said people of colour are inferior and we are still dealing with that today.

"While we cannot change history, and we cannot change the past, we are able to change the consequences, such as racism, for the better.”

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/subscriptions.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.