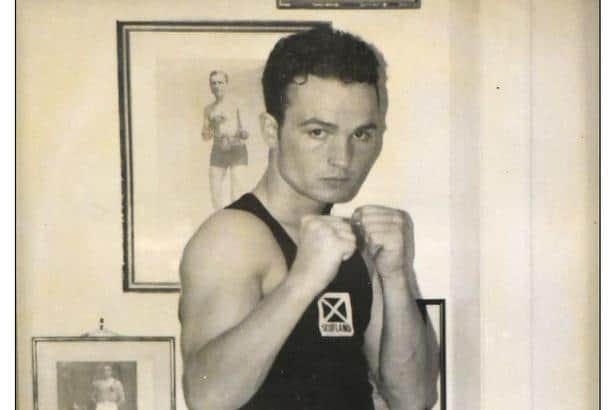

Bradley Welsh: The self-proclaimed ‘poacher turned gamekeeper’ known for his boxing talents, football hooligan days and inspiring community work

and live on Freeview channel 276

Born in Moredun in 1970, he studied at St Thomas of Aquin’s High School. He started boxing at the age of seven at Meadowbank and had taken part in about 200 fights by the time he was a teenager. Simultaneously he fell into a gang culture and followed his older brother into the Hibs casuals - the Capital City Service - when he was 13.

He later became involved in protection rackets and organising security at nightclubs across Edinburgh with the aim of shutting other venues down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the age of 18 he was jailed for menacing an estate agent, receiving a four year sentence of which he served 18 months.

In a 2019 interview with journalist James English, recorded just a few months before his death, Mr Welsh said: "I'm not proud of the levels of violence. I'm anti-violence now. I am a poacher turned gamekeeper but the person that I am is made from the experiences that I have had."

During this interview, Mr Welsh talked about young men in Edinburgh now getting involved in a “massive drug culture” and he said firearms were “very prevalent” in the city and across Scotland, and that this seemed to be the “new game.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn an episode of the documentary Danny Dyer’s Deadliest Men, Mr Welsh said part of being a football hooligan in the early 1980s meant having the right image by wearing the latest fashionable clothing. He said he was part of a group which carried out “smash and grab” raids at Jenners department store in the dead of night so they could steal expensive clothing. He claimed that they raided the store up to 20 times in one year.

As the house music scene arrived in Edinburgh in the late ‘80s, Mr Welsh said he saw an opportunity to capitalise on his position as club owners at the time were fearful of some of the Hibs casuals causing trouble on their premises. He went into business with a security company who provided doormen at some of the city’s main clubs. The company wanted more contracts, and Mr Welsh went out and got them.

Mr Welsh told the Danny Dyer programme: “I was 17 years old, just turning 18 and I thought I was Don Corleone.

"I thought ‘this is it, I can do whatever I want.’ I was being predacious with people, overpowering people - and it was a kick."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Mr Welsh said when he later ended up in Saughton prison at the age 18, he quickly realised it was not the life he wanted.

A prison warden there, Ian Duff, had represented Scotland at amateur boxing and spotted him straight away. Mr Duff, along with prison services, enabled Mr Welsh to keep up his training in the gym.

Mr Welsh told the Danny Dyer documentary that prison life was tough and he was involved in a couple of incidents inside. He recalled on one occasion being placed in a solitary cell in a straight jacket when his mail was dropped off for him. He said about 200 Hibs casuals had gone down to Millwall to take on a hooligan firm widely perceived as the toughest in the country, sending him postcards of all the places they stopped at on the way down there.

When he was transferred to an open prison, Mr Welsh was given day release to fight in amateur boxing competitions. He had three different fights which included beating the Italian amateur champion and winning the Scottish Western Districts Championship.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGoing on to box competitively after release from prison, he was the ABA Lightweight champion in 1993 as a member of Leith Victoria amateur boxing club.

After his release he also travelled to Italy, Turkey and Canada to box and was at the top of the amateur game before turning professional in the USA. There, he had ten bouts - a record of nine wins and one defeat - but felt the professional game was not for him because he saw too much focus on making money out of fighters rather than the sport itself.

During his interview with James English, Mr Welsh said he “made the mistake” of turning professional and that he should have gone to the Commonwealth Games in Canada in 1994 as an amateur boxer instead.

Mr Welsh also recalled spending six years “under the covers” where he spent time with family and friends. He later opened the Holyrood Boxing Gym in Craigmillar in 2006 to help young people who are economically and socially marginalised in his home city engage in sport and avoid a life of crime.

Movie role and community work

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe gym owner later landed a role in T2 - the Trainspotting sequel movie - alongside stars like Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle.

The opportunity came about after Trainspotting author and close friend, Irvine Welsh, brought director Danny Boyle and screenwriter John Hodge to his gym. Mr Welsh told the Edinburgh Evening News previously how the pair had participated in an event in 2014 which saw Mr Welsh make the Guiness Book of World Records after spending 24 hours non-stop in the ring as 360 people each worked the pads. The event raised more than £44,000 for charity.

The following day, Mr Boyle asked Bradley if he would like to audition for the movie for the part of gangland boss and sauna owner, Doyle. Mr Welsh said when he auditioned he “f***ed it up” and played it too aggressively. Two days later, at the book launch for an Irvine Welsh novel, he met the director again and asked for a second chance and made him a show reel - this time he secured the role.

In 2014, Mr Welsh also set up Helping Hands with Jim Slaven, a volunteer organisation which operated one of Edinburgh’s biggest food banks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe all volunteer Helping Hands group delivered free sports programmes for disadvantaged children - and during the pandemic last summer alone provided more than 120,000 cooked meals to those in need.

In a Youtube video posted earlier this year, Mr Slaven announced the group would come to an end. He said one of their aims was to inspire people to do more in their own communities and show it was possible to create change and not be dependent on the state, the charity sector, or on Helping Hands.