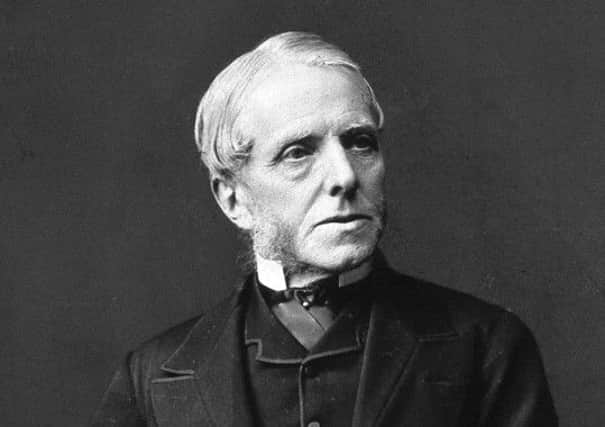

Henry Littlejohn helped win cholera fight

And for the people who lived a poverty-stricken existence in the shadow of deadly disease, the end would only bring them the indignity of being buried in a shallow pit.

Modern fears and the world of medical science are currently focused on the rapid rise of Ebola, on preventing its terrifying spread and caring for its victims.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s part on the ongoing a battle between mankind and our microscopic foes.

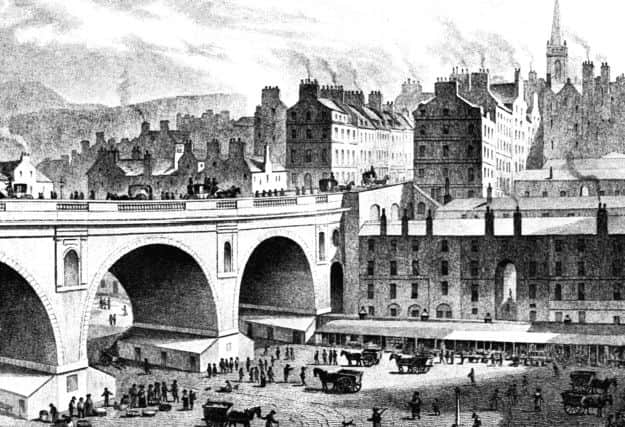

Certainly in 19th-century Edinburgh, all attention was on defeating an equally vicious disease, one that arrived from abroad, spread with deadly ease, bred in the filthy and stinking conditions in which poor families lived, ate and slept in, and which thrived in the city’s crowded stairs and tenements.

Cholera took five years to cross from Bengal to UK shores. With the potential to kill its victims within hours, it arrived in Edinburgh to find a perfect environment. Here it floated through the city’s pitiful sewage system and settled in the Old Town homes of the desperately poor, where dozens of families shared a common close and the stink of human waste clogged the air.

Once it had seized its victims, entire homes had to be quarantined then scrubbed, belongings and clothes burnt in a bid to halt its path of destruction – an eerie precursor to today’s Ebola threat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdinburgh had battled through one cholera outbreak in the 1830s when Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn was still just a lad. It struck again in 1849 and 1854, by which time he was Dr Littlejohn, Edinburgh’s first Medical Officer of Health.

It was the Capital’s good fortune to have one of the sharpest of minds of the age on its side. For under his direction, the city would become cleaner, healthier and, for many of its most vulnerable and pitiful citizens, far less deadly.

Littlejohn died 100 years ago last month, but as a new book of his life shows, the changes he instigated transformed and saved lives for years after he was gone. Under his guidance, the filth and stink that enabled diseases like cholera to flourish, were finally defeated.

Despite his achievements in making Edinburgh a safer place, there is little evidence in the form of tributes to his work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are no statues in his honour, even though his obituary in the British Medical Journal described him as “one of Edinburgh’s and Scotland’s great men”.

The Scotsman’s tribute was equally glowing: “Sir Henry Littlejohn was a unique personality. There was nothing commonplace about him. To his poorer fellow-citizens, ever a sympathetic listener, ever ready to help them in their distress.”

Indeed for many, disease and destitution were a distressing but seemingly unavoidable way of life, the risk of dying from a bug or virus which thrived in the unsanitary conditions in which they lived – smallpox, pneumonia, cholera – all part of their lot

Dr Littlejohn, however, had other ideas.

He helped create a new, far cleaner Capital thanks to his meticulous and forensic study of Edinburgh’s filthy water systems, drains, waste management. He even cast his expert eye over pollution, food hygiene, cemeteries, disease control and treatment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Richard Rodger, who wrote Insanitary City: Henry Littlejohn and the Condition of Edinburgh, along with co-author Paul Laxon, his work was so thorough and its arguments on how public health could be improved were so convincing, that the city council had little option but to agree to implement many of his often radical recommendations.

It meant his vision for a more sanitary city undoubtedly helped save hundreds from disease and despair.

Born in Leith Street in 1891, Henry Duncan Littlejohn’s father was a baker with a well-heeled client base in the New Town. Today, the ovens he used still exist inside what is now a bridal shop.

He went to the Royal High School and studied medicine at Edinburgh University before embarking on a career in which he juggled several key positions with vastly different remits all at the same time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis role as police surgeon for Edinburgh and Medical Advisor to the Crown in Scotland meant he was often called upon to give evidence at some of the country’s most shocking and gruesome murder and suicide cases.

He also taught at the Royal College of Surgeons where his students included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Sherlock Holmes creator is said to have used elements of Littlejohn’s character and style for his detective stories.

But it was his post as Medical Officer for Health of Edinburgh that helped improve life for thousands of fellow citizens. He was appointed in 1862 and quickly set about completing the momentous challenge of inspecting Edinburgh’s sanitation and compiling his findings in a massive document.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was at a time when city chiefs feared the possibility of another cholera outbreak – the most recent in 1854 had claimed several lives within hours of infection.

Littlejohn, a founder father of the Sick Kids’ hospital, set about analysing the connections between poor sanitation, crowded tenements and shared facilities with ill health and disease.

He shone a light on to work-related illnesses and food hygiene and even questioned how the city disposed of its dead by visiting graveyards at night and using a stick to check the depths of graves.

The result, says Richard, was a striking public health document that not only served its purpose in compelling city fathers to act, but today provides a unique vision of life in Edinburgh in the 19th century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLittlejohn had a clear vision of the impact of poverty on the city, one which some might argue is every bit as relevant today.

Mr Rodger says: “The report he produced in 1865 stresses how the wellbeing of the poor is central to the future of the city.

“What is quite interesting is that so many people are interested in death rates, but he was concerned with quality of life too. He wanted to improve that for the poor.

“He looks at employment, health and well-being.

“He argues that if you are poor and unemployed you’re not going to be eating well.

“That is central to this thinking. “

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe hugely detailed report, of which just 22 copies exist and which is reproduced in full in the book, breaks the city into small districts and reveals which parts of town were most at risk should a disease such as cholera strike – even down to individual closes.

“Abbey, Tron, Grassmarket, Pleasance . . . these are the areas he identifies as the worst and most insanitary,” explains Mr Rodger. “He shows for every one of these areas what the mortality is and the conditions were.

“One in particular, Middle Meal Market just off the High Street, had 248 people living in that stair alone, no sinks and no water closets.

“And he highlights another off the High Street, an eight-stair tenement, 134 people, that had just three sinks and three water closets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At another at West Port, there were 50 people, no sink or water closets. So you get a real sense of what the houses must have been like.”

As it transpired, his report was published just months before a fresh wave of cholera cases arrived in the city in 1866. While civic leaders were already under pressure to adopt his recommendations, the challenge of a deadly disease which thrived in the very unsanitary conditions which he had highlighted, made the need for rapid change even more vital.

Money restraints – not unlike today – proved challenging. However, Littlejohn had argued that key to improving the city’s fabric were its poorest people.

Confronted with his highly detailed investigations, and conscious that something had to be done to tackle the stench and squalor that engulfed the parts of the city, the council agreed to act. Soon houses were being knocked down and streets were being regularly cleaned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There had been cholera outbreaks. The city was aware that it did not have sufficient capacity in the Royal Infirmary to deal with cholera if it there was a serious outbreak,” adds Mr Rodger.

“They were very anxious about dealing with the problem.”

• Insanitary City - Henry Littlejohn and the Condition of Edinburgh is published by Carnegie Press, £24.99

Intravenous drips used in Leith

CHOLERA arrived in Britain from its source in India in 1831. The first confirmed British case involved a man in Sunderland.

By 1832, around 2000 people in Edinburgh had fallen victim, with just over 1000 losing their lives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt would be years before Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn’s vision for public health improvements would help in the battle to stave off cholera.

However, in Leith, where the daily arrival of vessels from foreign shores bringing potentially contaminated food and passengers, Dr Thomas Latta was treating patients with a new invention that would save millions.

Cholera victims suffered catastrophic loss of bodily fluids, the main cause of death. His invention, an intravenous injection of saline helped replace vital fluids.

He told of his findings in The Lancet but he contracted the disease and died in 1833. It would be decades before the treatment became a standard response to treating cholera – today IV drips are commonplace in hospitals around the world. Cholera returned to the area in 1849, again in 1854 and in 1866.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOld Town tenements and poor areas of Leith and Newhaven, with their lack of sanitation, open cesspits and human and animal waste rotting in the streets, provided a breeding ground for many diseases, including cholera.

Treatment typically involved washing infected closes and stairs with a lime solution. Sufferers and their families were placed in quarantine in their homes, and often their clothes and belongings were burned.