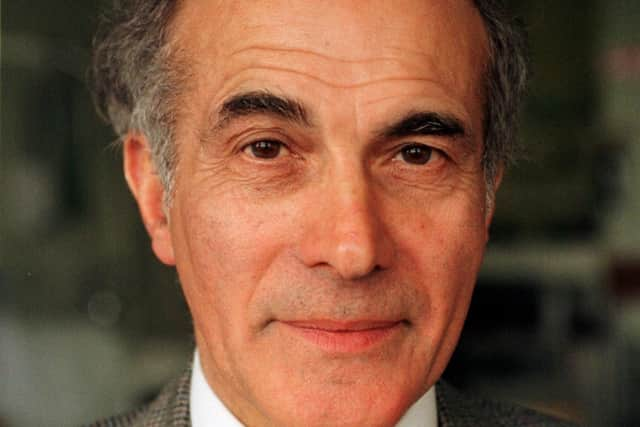

Eye surgeon Hector Chawla, former Eye Pavilion director, explains why Edinburgh needs a new eye hospital

and live on Freeview channel 276

Of all the special senses, the most precious is vision. Shut your eyes for two minutes then imagine what it would be like with the light shut out forever. It is fearful enough just to imagine and haunting for those who experience it.

Such total loss is fortunately rare; partial loss is unfortunately, rather common yet the ability to offer effective treatment has grown dramatically over the years. Such advance has not happened just anywhere and certainly not in all-purpose medical constructions scattered at random across the country. It is the result of specialist activity concentrated under one roof.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo deliver high technology eye care well today requires specialist doctors and nurses working in custom-built premises with dedicated theatres and equipment. To deliver it better tomorrow requires in addition, the training of junior staff and constant research.

Quite simply, the only way to produce the therapeutic magic that we all take for granted, is to continue with a concept that goes back centuries – to concentrate the whole enterprise in a single purpose unit.

The present eye hospital was state of the art in 1969 but it has now been worked beyond its sell-by date. The building was declared unsuitable in 2015. The roof leaks and the theatres on the top floor are only accessible for patients by lifts, which do not always work.

The removal of the Royal Infirmary to Little France raised another problem because the Eye Pavilion was now isolated. Many of the ophthalmic patients attending the present unit are elderly and likely to suffer vascular disorders and diabetes. Any acute medical emergency is an ambulance summons and a journey away from Little France and can be delayed further by the fragile lift system, should the emergency occur in one of the theatres. Even without the risk of litigation lawyers, it is not the best current practice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe idea of dispersing the eye services over a wide area into buildings and general-purpose theatres, not yet constructed has now surely been abandoned for reasons already well covered in the Evening News.

Whilst optometrists have taken over from GPs as the first staging post on an ophthalmic journey, their expertise is already being used to capacity and they cannot take over as a substitute for an integrated eye hospital and the majority work in a commercial setting.

Any provision that depends on already fully stretched ambulance crews to maintain a link between a patchwork of service units is doomed not to work. If to this is added the mental stress of surgeons, struggling up the motorway or having finally arrived, finding the theatre nurses not eye trained and the expensive specialist machines either broken or too complicated for the staff to set up, is only too believable. I have witnessed just such scenes made even more harrowing when the patient picks up distressing vibes from the general stress.

The case for a single unit based beside a major hospital has been made on countless occasions. In summary, operating theatres for eye surgery must be built for just that. Ophthalmic forceps and needle holders are not the same as those used by abdominal surgeons and they can only function if cared for by nurses who are used to the difference.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn addition, eye surgery depends increasingly on delicate expensive technology that can be very temperamental if badly treated. If it slightly doesn’t work, then it is more than slightly useless. They also require to be stored carefully and would not survive if having regularly to make space for say, colonoscopy apparatus.

Edinburgh, as a tertiary referral centre provides senior staff to allow peripheral units to survive – in Haddington, Fife and the Borders. To be able to provide such staff, it has to attract them in the first place. This it does by being the training centre of choice throughout the United Kingdom. Any attempt to break up the present unit or to fail to provide a replacement worthy of the Capital, would at a stroke destroy a reputation built over more than a century.

Even within its ageing walls, the Eye Pavilion is at the cutting edge of giving its staff even more to offer. It was the first unit to extend the role of the nurse and to run a teaching programme for the Ophthalmic Nursing Diploma.

Research is a painstaking enterprise, coupling hard work with a mind open to ideas previously regarded as heresy and also capable of seeing connections invisible to everyone else – the Eureka moment. Thereafter comes the obligation to back up the revelation with science, a process possible only in a single purpose unit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor example, the lens implants that now give such magical post cataract vision began with the observation that fragments of Perspex from aircraft windscreens entering pilots’ eyes during the 1939-45 war did not excite a foreign body reaction. In other words, they were tolerated within the eye as a fragment of brass or steel or anything else was not. And at this point, the observed fact might have slipped into the litany of missed opportunities if someone had not made the mental jump – ”a fragment of windscreen accepted by the eye, why not a fragment shaped like a lens in place of a cataract?”

But it took 30 years of attempts after that within a hospital setting to work out the pitfalls and to give us what we assume as a birth right today; they continue to be improved and Edinburgh was one of the first places in Britain to try them. Such an advance could not have been made in a dispersed setting. That is why we urgently need our new Edinburgh Eye Hospital at Little France.

Hector Bryson Chawla, OBE FRCS, was formerly a consultant at Edinburgh’s Princess Alexandra Eye Pavilion and director there for ten years until 2010.