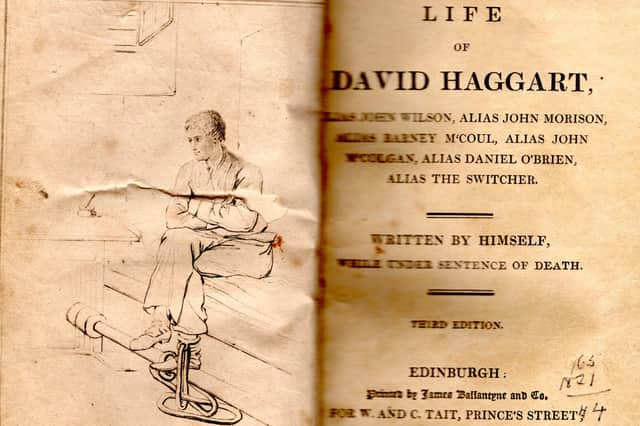

Confessional book penned by Edinburgh murderer hanged in 1821, bought on eBay for £20, poses literary mystery

Books written by convicted murderers are uncommon, and this one might well be unique in that Haggart was just 20 years old at the time, and that he was said to have been executed just a few days after completing it. I bought this book for £20 and set about learning of its contents.

David Haggart claimed to have been born at Goldenacre, near Canonmills, on June 24 1801, the son of the gamekeeper John Haggart. He did well at school but left at an early age, being by then able to read well and write in a tolerably good hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShowing early criminal tendencies, he stole a bantam cock when he was only 10, and later successfully burgled a shop. At the age of 12, he got drunk at the Leith Races, finding himself a drummer boy in an army regiment when he sobered up. His military service was not a lengthy one, however, since he obtained his discharge when the regiment was ordered back to England.

After attending school for nine months, learning arithmetic and book-keeping, he was apprenticed to a firm of millwrights. But the firm went bankrupt in 1817 and David was out on the street again. Together with an older Irish boy named Barney M’Guire, he took to pick-pocketing, lifting £11 from the pocket of a punter at the Portobello Races. The two villains next went on a pick-pocketing tour of the Borders, attending markets and fairs with good success: Haggart was happier than ever after relieving a wealthy gentleman of a pocket-book containing £201.

Haggart and M’Guire next took to burglary, breaking into a house in Durham, knocking down the householder and stealing £30. This time they were caught and sentenced to death at the Durham Assizes. But the nimble Haggart managed to escape from Durham Gaol, bravely returning with a spring-saw and rescuing M’Guire as well. Their life of crime continued until M’Guire was caught by John Richardson, the sheriff-officer in Dumfries, and sentenced to 14 years of transportation to Botany Bay.

Haggart was also arrested, but he once more broke out of jail. By now declared an outlaw, he was again arrested and put in the Dumfries Tolbooth. On October 10 1820, when the turnkey Thomas Morrin passed with a plate of soup for another prisoner, Haggart knocked him out cold with a large stone wrapped in a piece of blanket, stole his keys and escaped once more.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few days later, when hiding in a haystack to keep one step ahead of the law, he heard a woman ask, ‘Has that lad been taken that had broken out of Dumfries Jail?’

When a boy answered, ‘No, but the gaoler died last night’, Haggart knew that this time he was in serious trouble.

A murderer now and a wanted man, he returned to Edinburgh, where he was dismayed to see a ‘Wanted’ poster offer £70 for information leading to his arrest.

Teaming up with another pickpocket named James Edgy, they successfully robbed and beat a farmer in Perth, before escaping from Glasgow to Belfast. Edgy was soon knocked out and arrested by a sturdy police constable, but Haggart went on picking Irish pockets with some success.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, after a Dumfries man spotted him, the hue and cry was up for ‘Haggart the Murderer’ and he was once more arrested. An attempt to escape was impeded by a hard blow from a shillelagh and, after being identified by the Dumfries police officer John Richardson, he was taken back to Scotland, heavily fettered since Richardson knew his escapological tendencies.

In Dumfries, ‘Haggart the Murderer’ was seen by thousands of curious people. In Edinburgh, he was incarcerated in Calton Prison, found guilty of murder on June 11 and executed at the head of Libberton’s Wynd on July 18, 1821.

For Haggart’s other adventures, his autobiography is the only source. No less an authority than the old Dictionary of National Biography spoke highly of the literary efforts of the young Scottish thief: ‘It is a curious picture of criminal life, the best, and seemingly the most faithful, of its kind, and possesses also some linguistic value, as being mainly written in the Scottish thieves’ cant, which contains a good many genuine Romany words.’

In contrast, the legal luminary Lord Cockburn suspected a forgery: the book was ‘a tissue of absolute lies, not of mistakes, or of exaggerations, or of fancies, but of sheer and intended lies. And they all had one object, to make him appear a greater villain than he really was.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA historian who wrote up the case for the Police Journal of 1929 chose the middle ground: he found Haggart’s narrative largely credible although unsupported by solid evidence.

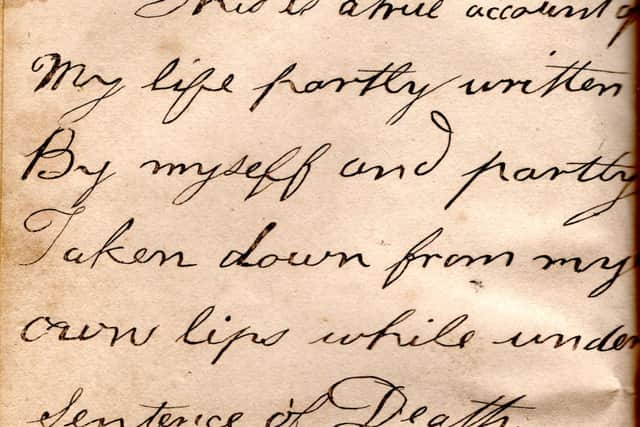

Haggart claimed to have partly written, partly dictated his book, which is 162 pages long. But according to an account of his trial in the Caledonian Mercury of June 16, 1821, he had stated upon oath that he could not write.

There are two accounts of his activities awaiting execution, in the Caledonian Mercury of June 21 and the Glasgow Herald of June 25, 1821, but neither mentions any literary endeavours. Was the book in fact ‘ghosted’ by some old criminal associate of his?

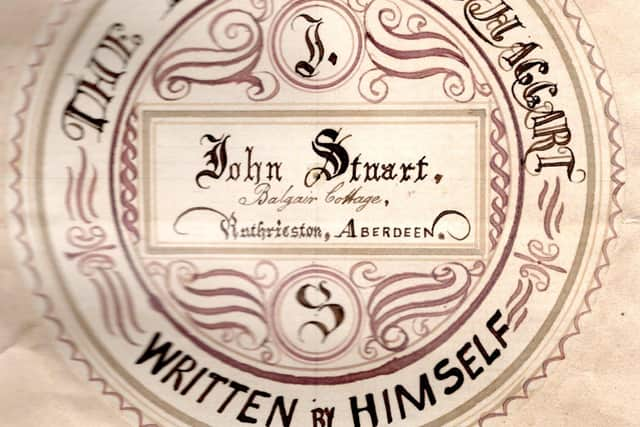

Whether it was a successful literary hoax or the genuine article, it enjoyed considerable success, going through several Edinburgh editions already in 1821, and appearing in pirated English reprintings as late as the 1850s. Today it is quite rare, however, and a good copy of the 1821 edition will set you back £300, unless you defile your bookshelf with an ugly modern version, or your computer with that nightmare for every proper bibliophile, a Kindle Book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJan Bondeson’s Murder Houses of Edinburgh is available at www.troubador.co.uk/bookshop/history-politics-society/murder-houses-of-edinburgh/