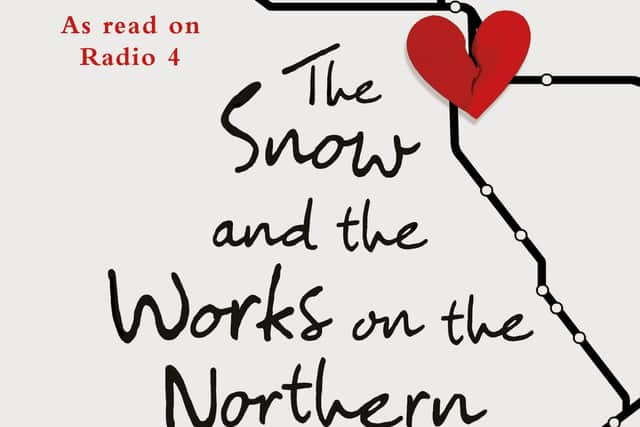

The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line, part three: Love is in the air

Then I’d returned to London and had an unexpected fling with a Danish astrophysicist called Mats, before moving on to a bearded and more sensible man named James who was doing a PhD and had been doing so for years. I imagined he would be about forty-six before he submitted it. He used to make a lot of gnomic and profound remarks and he also sometimes made me laugh. But after a while his immense, serious wisdom had begun to weigh me down, the way too much snow weighs down a too-thin branch, and I moved on from him, a little sadder but, paradoxically, lighter of heart.I was alone for a few months after that, and then I met Simon: we met one night in The Olive Branch, an Italian restaurant round the corner from my flat, where he worked as a chef. I had gone in alone, a young woman about town, and ordered salted cod by mistake, and after I’d returned it and he’d appeared at my table with a replacement bowl of spaghetti al pomodoro and said he’d made the pasta himself, not from wheat but from spelt, it was pretty much love at first sight; I suppose it was what is called a coup de foudre. Even though we were not actually alike at all, it soon transpired, and we didn’t even like doing the same things. He was an active sort of person, whereas I’d always preferred observing other people being active.

He liked driving his boss’s Alfa Romeo around town, and I liked going to the cinema and watching other people driving their cars around. He liked outdoor pursuits – foraging, hiking, wild camping – while I couldn’t stand windswept walks up uneven gradients, or eating fungi that might kill you, or listening to disconcerting noises outside a tent at three in the morning.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut love is not concerned with such differences, of course; love does not have motives or reasons or ambitions or even shared tastes. We’d simply fallen for each other: we were yin and yang, light and shade, Mr Sunshine and Mrs Rain in their little wooden house. It didn’t seem to matter that he was pragmatic and I was a conjecturer; that he made things, and I wondered about them; that he was an outstanding and inventive cook, whereas I was mostly a compiler of sandwiches. At the end of the day I would turn the key in the lock of our front door (we moved in together less than a year after first meeting), and would feel happy if he was already home, frying shallots or chopping herbs from the little pots he kept on our kitchen windowsill.Of course, I did worry from time to time about the ways we were different, and perhaps, it occurred to me later, I should have worried a little more as the months went by.

Maybe if I’d thought, for instance, about his decision not to go with me to my grandfather’s funeral that autumn because he’d hardly known the guy; or reflected on the camping trip we had gone on just two days later, because camping was extremely important to him – and how, although I loved the pine-scented woods and the craggy hills and the birds flapping around the sky, I’d felt a terrible, lonely ache in my chest, and it had been clear to me within five minutes of pitching the tent that he was going to enjoy himself a lot more than I was.

I’d taken my guitar along to play a few songs, but even as I sat there, picking out Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd tracks on a slightly sloping patch of damp grass, I knew I could never be truly excited about a holiday that involved washing up in a stream with a Brillo pad and gathering sticks; I knew that, at heart, I really wanted to be at home, missing my grandad, and watching QI in my slippers.

We spent a lot of our first day trying to work out where we were in relation to the nearest village (we were fourteen miles away) and boiling up farro grains in a tiny saucepan, the clip-on handle of which kept falling off. Then halfway through Day Two, scouting in the woods for a suitably private patch of bracken, I’d peered up to witness a farmer appear puce-faced over the brow of the hill on a quad bike, yell something and wave his arms, before a flock of about 50 sheep came careering into the field where we’d pitched our tent.‘The thing is,’ I said to Simon that night, as we sat in the greenish shadows, ‘we do actually live in the twenty-first century. So why pretend we still live in the Bronze Age?’He looked at me. He looked very serious, almost sad, as if some fundamental truth had just occurred to him, about the many ways we would never understand each other. Maybe he was thinking: If we were depending on you for survival we’d have another 48 hours, max. But then he smiled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Come here, twenty-first-century girl,’ he said, unzipping the sleeping bag which he’d bought especially for me, because it was a four-seasons tog rating, and I slid along the sloping nylon groundsheet towards him and slung my arms around his neck.The thing is, we were not always on the same wavelength. But this didn’t mean I didn’t love him. It did not mean I didn’t care.Then, one afternoon a few weeks later – the same afternoon (it transpired) that Helen returned to my life – we had an argument…

Tomorrow: The Argument

The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line, by Ruth Thomas, published in paperback by Sandstone, priced £8.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.