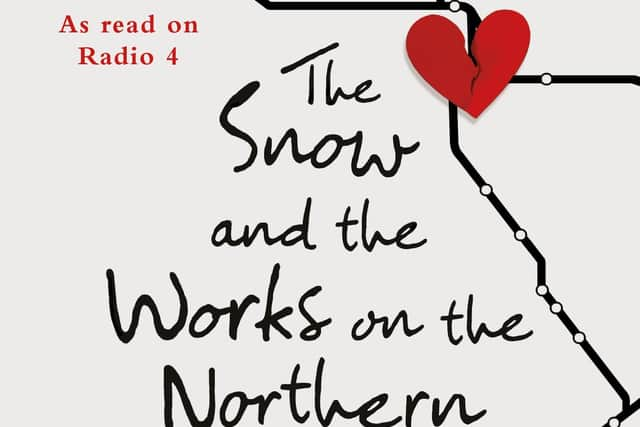

The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line, part two: 'I was still living and breathing in some hospital ward...'

A little later I was somewhere, of course: I was not in heaven with my grandfather, I was still living and breathing in some ward in Dulwich Community Hospital.

I was in the same old world and it was late December, and Simon was so unscathed he’d already left Outpatients and headed home on a bus. He’d gone with Helen Hansen, in fact. Because it had been her. And really, it was quite a miracle that neither of us was not more badly hurt.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHelen mentioned this herself, when she put her head round my door at work a few days later; she’d turned up again for one of the Trustees meetings she kept going to.‘So someone was looking out for you last week, Sybil!’ she said, in her sassy way. And she smiled that big smile of hers.‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I suppose they must have been.’

I looked down at my desk-top, and couldn’t think what else to say. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘thanks for coming to the hospital with us, Helen. That was nice of you. As neither of us was particularly compos mentis at the time.’ Because I’d been brought up to be polite - even to people I didn’t actually like. Then I smiled briefly and got on with my work, and everything around me had looked much the same, for the next few weeks. It all was much the same. I just hadn’t realised it was about to look different.I hadn’t seen her for ages, before that. Not for nearly seven years. But whenever I thought back to those days, I’d remember how she had seemed to quite like me. She’d made a strange beeline for me – something I’d never really understood.

I’d been a young first-year student, awkward as a goat, and she was a glamorous academic heading towards a doctorate. I’ve since learned that some people operate like this. They like to bask in other people’s reflected lack of glory. But I didn’t know this at the time; I’d just accepted her attention with bafflement and a vague wish to get away. Two things stood out in my memory: once, during a tutorial on funerary urns, she’d flattened a wasp with a plastic Helix ruler, squashing the life out of it rather than simply letting it fly through the open window and, halfway through our first term together, she’d started calling me Sybil the Blind Prophet.

This was, she said, an affectionate joke.

‘It’s meant to be a compliment, Sybil! It’s because you know so much! You seem to know things by some mysterious osmotic process, and I can never work out how you do it!’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’d always thought that was peculiar, too. My ability to retain any information at all really seemed to bother her.At the end of my university days I’d gone to Swansea to do a post-graduate degree in Norse and Celtic Mythology, and although I’d heard occasional news of Helen’s starry progress through academia via a journal called Archaeology Now!, which my old department intermittently brought out and sent to me via my parents’ address in Norfolk, I’d assumed our paths would not cross again.

I was perfectly happy about this: quite content to hear news of Helen through the pages of Archaeology Now! It was, for instance, where I’d first learned of her unexpected departure from my old university in order to take up an exciting new role as Director of the London Museums Interpretation Centre, in Tooting. I’d opened that issue during a weekend stay at my parents’ house, and there she was, in the centre pages, standing beneath the diplodocus skeleton in the grand hall of the Natural History Museum. She was clasping a champagne flute, her blue eyes flashing, her jaw set at an ever more resolute angle.

‘I see my role as facilitating the various commercial opportunities available to museums and academic institutions in the twenty-first century, while remaining sympathetic to and respecting the core values and aims of historians and archaeologists...’ she’d proclaimed, in an interview beneath this picture.

The London Museums Interpretation Centre (LMIC, for short) was, apparently, a much-needed new umbrella group for smaller British museums, channeling funds, arranging networking events and reaching out to new audiences and consumer markets.‘Well, she looks like a force to be reckoned with,’ my father had observed, peering over my shoulder at the photo. ‘Tooting, though? Seems an unlikely place.’‘But where’s a likely place?’ I asked. ‘For someone like her?’‘I don’t know, New York? Tokyo? Paris? Somewhere glamorous.’‘Oh.’He glanced at the picture again. ‘Helen: the face that launched ten thousand ships.’‘One thousand,’ I corrected him.‘What was it she used to lecture you on?’‘Beakers. As in The Beaker People.’‘Oh.’He looked vaguely disappointed. I had not done much myself during my years in Swansea, after the perfectly respectable 2nd class Honours degree I’d wrested from the jaws of the 3rd class one Helen had (as I later discovered) recommended. I’d read The Mabinogion and the Arthurian legends and written a dissertation on The Book of the Dun Cow(a book I’d initially assumed was about a cow: I was wrong.)I had fallen in love for a while with a long-haired Irish legends specialist who’d smoked a lot of weed, never got out of bed before 3pm and owned a lime-green mug that said Time and Relative Dimension in Space. I don’t know why the memory of that mug loomed so large in my mind, it just did.

Tomorrow: Meeting Simon

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Snow and the Works on the Northern Line, by Ruth Thomas, published in paperback by Sandstone, priced £8.99