The weird, wonderful and shocking finds beneath Edinburgh's streets

From the days when he had to walk parts of the main Victorian sewers checking for any cracks to the times he saw colleagues sieve the city’s raw sewage to look for any valuables they could sell on, Stewart has seen it all.

Following more than four decades dealing with the murkier side of the Capital, including his own involvement in a shocking murder case, Stewart will retire at the end of this month.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 61-year-old has been part of a changing landscape as responsibility for water services switched from regional structures to the nationwide publicly-owned utility Scottish Water, formed in 2002.

And despite decades of being asked why he chose to work with waste water – “someone has to,” he says – Stewart has taken a real pride in working in a key service that impacts on everyone’s lives.

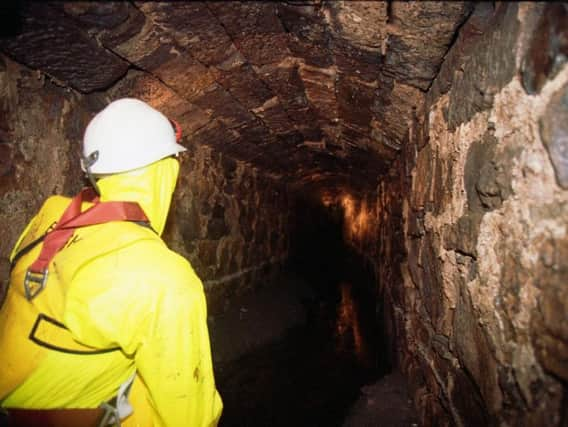

He said: “You could never call what I did glamorous, but it is fascinating. And to have lasted this long the secret has been not thinking about what it is you sometimes have to wade about in – and it’s not for people with claustrophobia.”

Stewart, from Edinburgh, started his four-decade career in 1976 as a civil engineer technician at Lothian Regional Council’s Department of Drainage. Ten years later he was a Works Supervisor, repairing and maintaining the sewers and drains.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “Every summer we had to inspect the trunk sewers, some as small as 4ft and some as big as 9ft. It was smelly and wet but it had to be done. There was no fancy equipment back then and we used a hand-held tape recorder wrapped in polythene to record the defects.

“That’s the biggest difference over my years, the fact technology has moved on so much.”

Another issue was the hard graft that was sometimes required in the 1980s to fix a sewer collapse.

He remembers one at the rear of a property near the Dean Bridge which was on top of a small cliff above the Water of Leith. He and his team had to hand-dig five metres to get to the sewer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey then had to crawl along a 900mm high tunnel than ran for 20 metres along the back of the houses to another 3 metre deep shaft only 1.2 metres wide and the blockage was at the bottom .

“We had to hand-dig day after day and every morning pump out the waste water from the area before we could start digging,” he recalls.

Over the years his team came across lots of unusual items, as Stewart revealed: “Back then we had to clean some sewers with shovels and wheelbarrows and have seen everything from false teeth to toys to cutlery and dead pets. There were always so many pieces of jewellery, mostly old rings. I know some of the men would sieve the sewage to look for valuables before taking it all away.”

Stewart says much of the city’s sewer network dates back to the mid to late 1800s – and astonishingly some of the complex brickwork is “quite beautiful” and “amazingly, in perfect condition”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “Most people never think about what happens with their waste water, but as an engineer I find it fascinating the way the sewers interconnect and bend and flow to get what we put down the loo back out to sea. In some parts it travels many miles and it needs a very well designed network to work right.

“Edinburgh has expanded beyond belief and the sewer network has got longer and in places much bigger to cope with demand. It has been so interesting helping to play my small part in designing parts of it and knowing my job is an essential part of daily life.”

Over the years Stewart, a keen sportsman, has worked with Scottish Water colleagues to help raise many thousands of pounds for the charity Wateraid.

In 1999 he took part in the Everest Marathon, which included hiking at altitude for nearly three weeks just to get to the start.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe completed the Six Peaks Challenge – climbing the highest peak in each country of the UK and Ireland in 72 hours. He also visited Uganda to help build water projects. He received the Presidents’ Award from WaterAid patron, Prince Charles, for all his fundraising efforts.

And he plans to continue taking part in lots of sports “full time” after he retires. He is already planning an Edinburgh Sewer Cycle Tour for later this year when he will take a group of cyclists on a 30-mile circuit of the sewer network in the city and surrounding area.

He said: “It seems I cannot say goodbye to these sewers – I can’t wait to show them the routes and explain how it all works.”

Stewart, who grew up in a two-bedroom flat on the Royal Mile with seven family members, admits it may have been the fact he had to traipse to an outside loo – shared with his neighbours – which promoted his career in the water industry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “After growing up like that you never ever take water for granted.”

Bill Elliot, National Stakeholder Manager at Scottish Water, said: “Stewart’s hard work and dedication over the last 43 years and his service to customers has been truly remarkable.

“Everyone who has worked alongside him through the years has gained from his knowledge and expertise.”

Blocked drain led to one of Edinburgh's enduring murder mysteries

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor Stewart Imrie, the morning of August 15, 1996, started normally as he responded to a routine call to deal with drainage problems in the city.

But within minutes of arriving at the rear of a tenement in Clerk Street, Stewart and his colleagues were forever linked to one of the Capital’s most baffling unsolved murders.

As his works crew lifted the manhole cover they saw a woman’s arm sticking out of the water deep below.

They immediately raised the alarm as word of the gruesome discovery spread rapidly through the area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStewart said: “A woman in her 20s had been killed and placed down there. My team had to pull her out. It was a very, very sad day. We found out she had been murdered, the story was in the papers for weeks.”

The body, partly wrapped in wire netting, was that of missing catering assistant and renowned karaoke singer Deirdre Kivlin, pictured above.

The 24-year-old’s skull had been split in two and she had to be identified from dental records after being in the water for up to five weeks.

Painstaking detective work led officers to homeless glue-sniffer Scott Ballantyne, right, then 26, who used to sleep rough in Deirdre’s stairwell at 100 Clerk Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProsecutors claimed Ballantyne bludgeoned Deirdre with a brick and robbed her before hiding her body. Deirdre’s DNA was found on his coat –

but Ballantyne was cleared of her murder on a not proven verdict and no one has ever been brought to justice for her death.