Remembering the world's first shale oil boom

Professor Iain Stewart is standing astride centuries of human endeavour; a man-made promontory of pink mineral deposits which reaches nearly 100 metres towards the sky, a mountain of rocky leftovers from the spoils of Scotland’s first oil rush.

To compare the Greendykes and Albyn bings on the outskirts of Broxburn – or the Five Sisters deep in West Lothian – to Egypt’s historical wonders seems a bit of a claim for what many regard as industrial scars on a rural landscape. But the geologist and documentary presenter goes further, describing them as similar to Ayers Rock and admitting that despite the many fascinating places he’s been in his career he’s seen “nothing quite like this. What a crazy landscape – it looks like a Star Trek set.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCertainly the story he tells of how shale oil changed this part of Scotland – which is broadcast on BBC2 Scotland at 9pm tonight – seems other-worldly in comparison to modern-day Broxburn or Addiewell, which was once the site of the world’s biggest oil refinery, built in 1865.

The programme spans the 100 years that saw West Lothian become the centre of an oil industry which lit hundreds of thousands of homes; exported oil to Europe and Scandinavia; fuelled Britain’s naval fleet during the First World War and created vast wealth for some and lifted others out of poverty – at least for a while.

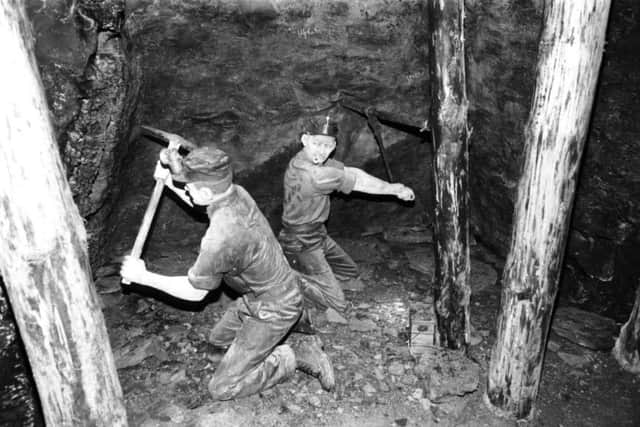

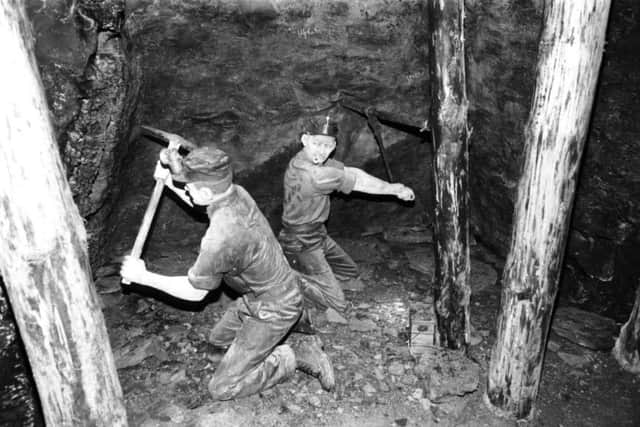

He speaks to former miners, hearing how they faced the risk of death every day as rocks were exploded to release the shale, before their back-breaking work began, digging out the vital mineral by pickaxe and loading it on to carts.

There is tragedy of course – 15 men died in an explosion at Burngrange mine near West Calder. And there is war: those who played in the Broxburn pit band became the recruiting band for the Royal Scots; six fell on the battlefields of France.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMost of all though there is community spirit – and a celebration of the innovation which made the industry the pride of Britain in the Victorian era.

“More than 100 years before the discovery of oil in the North Sea, the world’s first commercial oil strike was made in the flat lands between Scotland’s two largest cities, signalling the start of an oil boom which would transform the landscape,” says Prof Stewart. “Workers flooded in and towns sprung up overnight, Fortunes were made and lives were lost.”

It turns out that West Lothian became the centre for the shale oil rush in the late 1800s because 350 million years previously there had been a vast lagoon in the area, surrounded by forest. Over time the mud which settled at the bottom of the lagoon became full of dead plants and animals which decomposed to form oil shale.

The rural landscape and society of West Lothian was transformed by the discovery of torbanite and the genius of one engineer and entrepreneur. As Prof Stewart says, at that time it was felt anything was possible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says: “Victorians had this unshakeable belief in the power of progress. One of those was James Young. He was the world’s first oilman.”

Torbanite was discovered just south of Bathgate and found to be rich in oil – a stockpile burned for weeks, the oil running into the River Almond.

Working with chemist Edward Meldrum, Young discovered a way to extract the oil and then to refine it for commercial use. “It wasn’t quite like getting blood from a stone, but it wasn’t far off,” says Prof Stewart.

The pair built a refinery, known as the “secret works”. Factories were rare in the area – Bathgate was a weaving village. Workers were sworn to secrecy and there was high security.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom lubricating oil, Young realised that he had created a new lighting oil which was much safer than the commonly-used whale oil. He realised there would be demand for paraffin lamps for people’s homes, so he set up a lamp factory, too.

“He changed the way people set up their homes, lived their lives. It made him and his partners very wealthy men,” says Prof Stewart.

As Young’s torbanite seam began to run out, shale was discovered in seemingly untold reserves. By now Young wasn’t alone in realising its potential. In the 1860s, Robert Bell opened an oil shale mine and refinery in Broxburn and turned the rural village into Scotland’s boomtown.

“Within a short space of time it was producing 10,000 gallons of crude oil per day. It must have been like the Klondyke then. Transforming the village into shale-opolis, mines, refineries and oil works began emerging all over the landscaped and those majestic bings began to appear.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAddiewell, an even smaller village, saw a greater change as its population went from 23 to 1300 in just six years. Many of the newcomers were from Ireland, and despite their long hours and hard toil, every day after work they took the shale deposits to fill in marshland so they could build a church.

Not that they were always welcome, as Prof Stewart discovers – their acceptance of slightly lower wages strained community relationships.

However, community spirit was forged by the hard work. Gala days became a major focus of the year, bringing people together and creating miners’ bands, such as the Broxburn & Livingston Brass Band which still goes strong today.

Women began to work in the mines – though not underground – but by the time men came home from the trenches of the First World War they found that oil shale had been usurped by cheaper crude oil which was being produced far more easily in the US and the Caspian.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was unrest – wage cuts caused strikes and parish councils refused to give benefits to miners’ families. Despite government subsidies, the 1920s were hard and mines began to close. Westwood was the last to close in 1962.

Still, the shale deposits were put to some use, as the raw materials for new roads and housing foundations.

“The story of Scotland’s first oil rush is one of an epic 100-year struggle to exploit our natural wealth,” says Prof Stewart. “Scotland’s oil shale story is fading away, yet the ingenuity and sheer hard graft of those times has helped build modern Scotland.”

• Scotland’ First Oil Rush is on BBC2 Scotland at 9pm tonight.