When a tunnel ran under the Forth

It was early morning, the last stage of a remarkable job was nearly done and now, deep under the Forth, choking dust in the air and with rubble underfoot, two men wiped the beads of sweat from their brows, the grit from their eyes, and shouted a friendly, sing-song “Helllloooo” at each other. Bathed in the dim glow of miners’ lamps, this was surely among the most remarkable of greetings.

For this was 50 years ago, and the final task in an astonishing engineering mission had just been achieved – to chisel a winding tunnel beneath the Forth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeandering under the estuary, from Bo’ness on the edge of West Lothian to Valleyfield in Fife, two years in its execution, the underwater tunnel did what many had long dreamed of doing.

It created a shortcut linking the south side with the north. Yet while thoughts today turn to the openeing of the new Queensferry Crossing, it’s likely that few will even be aware of a fourth Firth of Forth connection at this end of the estuary.

For while the tunnel through rock beneath the water was ground-breaking in more ways than one, it was never intended for public use.

Today, sadly, anyone trying to use it – indeed, even attempt to find it – will be sorely disappointed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

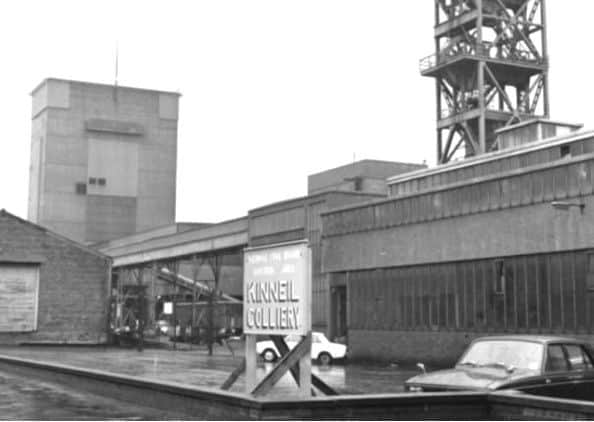

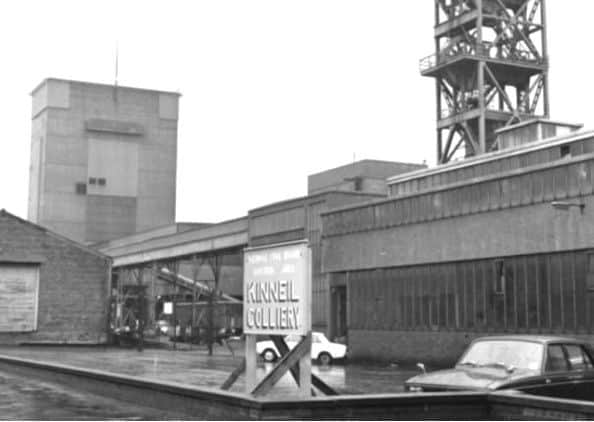

Hide AdJust like the once thriving coal industry it served, the tunnel is now a fading memory, the shafts which led to it filled in and capped, the iron props which supported it inside almost certainly collapsed. By now the grey waters of the Forth will have claimed ownership and the crossing which once linked Kinneil Colliery in Bo’ness with Valleyfield pit in Fife, enabling its engineer Alistair Moore to shout his friendly greeting to his Fife neighbour and eventually coal trucks to pass to and fro, is no longer passable.

Alistair spoke to the Evening News in 2015 when he was 82. Living just a stone’s throw from where the colliery once stood, he could still recall the run-up to the historic moment – particularly as it had the indecency to coincide with his holiday plans – and the laborious, brain-testing preparations that went into his remarkable feat of engineering.

It was his unbelievably accurate calculations that meant the Valleyfield side of the tunnel connected to the Kinneil side with just the tiniest of margins. Yet among his biggest concerns at the time was how the final stages of work clashed with his plans.

“I was due to go on holiday,” he said, remembering back to late April 1964 when teams which had set out underground from Valleyfield and Kinneil were busy carving the final few feet under the Forth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I thought there was about 25 feet to go but I was going on holiday for a fortnight. My boys were young and we were going up to Aberdeenshire.

“The manager said ‘you’re not going anywhere, you’re staying here’. So I thought, ‘let’s get this done quickly so I can get my holidays’.”

Work at the Valleyfield side was halted and a Sunday shift of Kinneil workers battered through the last remaining stretch. He remembers racing to work at 6am next morning, April 30, to make his way to the scene of the final push.

“The boys were working with a big jack hammer which used compressed air. You couldn’t hear a thing,” he said. “I’m watching them and all of a sudden they were crashing in and there was a wee hole, just three inches in diameter and the drill went shooting through. We were in. “I put my mouth near the hole, as close as possible and I shouted ‘Helllloooo’ and got back this ‘Helllloooo’ from the other side.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe tunnel was the idea of the National Coal Board, designed to make use of the modern coal preparation facilities at Kinneil in favour of the outmoded plant at Valleyfield which was so dated that it was under threat of closure for health and safety reasons.

If joining two stretches of tunnel together sounds straightforward, Alistair said this was a task that involved not only getting the two ends to arrive at the same point, but also to ensure their levels were spot on.

As it was, they connected with a mere six inches difference – an incredible achievement given the then 32-year-old Heriot-Watt graduate’s calculations had been worked out with brain power, pencil, paper, plumb lines and the trig pillar situated on top of Arthur’s Seat. “

This wasn’t a tunnel in a straight line,” said.

“It wasn’t a route that you could ever just walk straight through. This was a tunnel associated with the coal seams under the Forth, with angles and slopes – a fairly convoluted system of roadways.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It needed ‘manholes’ every 30 yards – a cubby hole for a person to shelter in when a locomotive was coming through.

“It wasn’t at all a straight tunnel.

“As the crow flies, the distance between north and south would be about 1.8 miles, but we had about 2.5 miles of works to make the connection between the two. “We had to get the levels correct, which it was to about six inches – quite a nice feather in our cap. The next was to make sure that the connection from Valleyfield was in line with us. And it was.”

These days, lasers and computers would be used to ensure pinpoint accuracy. Alistair and his engineering colleagues’ tools were far more basic. For a start, they had to correlate the mines and underground workings to the Ordnance Survey National Grid, using established pointers, such as the trig pillar on Arthur’s Seat, church spires and, for underground measurements, piano wires hung with 150lb plumb weights.

Steel bands used in the process were, incredibly, measured using two brass plaques at the foot of The Mound which are precisely 100ft apart. And even then, when the heat underground stretched the bands, Alistair’s calculations would have to be redone, again and again. “There were no computers or calculators,” he shrugged.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All we had was a machine called a Brunsviga, you put one set of numbers on one side and pulled a lever and the other figures on the other side and pulled the lever again a certain number of times, depending on what you were working out.

“It was primitive. Not just that, most people would use four-figure log tables, mine was eight-figure, the log book was four inches thick.”

The first small breakthrough joining Fife with West Lothian having been made, the two mine managers were called to the scene along with union officials, the provost of Bo’ness, and, naturally, a reporter from the Edinburgh Evening News and Dispatch to witness the next stage.

A 23-year-old Kinneil miner called Martin ‘Tiger’ Shaw was enlisted to do the honours, while on the Fife side, Valleyfield miner Andrew Drysale, 34, waited patiently.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The drill in the hands of Tiger Shaw began biting through the thin sandstone shell, the last barrier in the tunnel link at 10.30am,” reported the paper later that day.

“Three minutes later, the lamps of the Valleyfield squad blinked through the gap in the rock and Shaw and Drysdale were face to face.” The pair are said to have “grinned dustily at each other” before moving aside so the two pit managers, David Archibald of Kinneil and Norman Wallace of Valleyfield, could reach through the hole in the sandstone rock to shake hands.

“I hope you have plenty of coal for me,” said Mr Archibald, thinking forward to the locomotives that would pull Valleyfield coal to his Kinneil plant. Alistair, meanwhile, had already seen enough. He said: “I didn’t bother with all that. I was off on my holidays.”