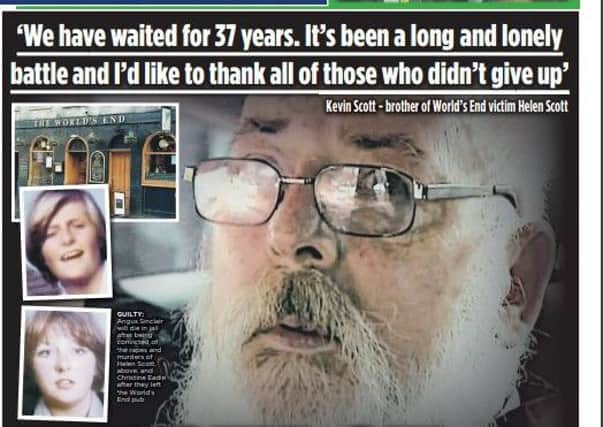

Revealed: How advances in forensic science and technology helped catch World’s End killer Angus Sinclair

Police worked tirelessly to crack the case, passing down evidence and theories from one generation of officers to the next.

But this old fashioned detective work - talking, probing, pushing for answers, hunting down clues and acting on sheer instinct borne from years of experience - could only take the investigation so far.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd eventually the major breakthrough would come thanks to a very modern form of detective work, The key to finally securing Sinclair’s guilt came in the form of what could only be described as a glorified torch. Unavailable at the time of the first World’s End trial, Crime-Lite uses LED (light-emitting diodes) to produce high-intensity light of varying wavelengths.

Once shone on a piece of evidence - such as a murder victim’s coat or the knotted tights used to bind hands - potential DNA glows like a neon beacon, directing forensic scientists towards areas to check which, otherwise, they could never have spotted. In the case of the World’s End murders, it would reveal evidence which would prove impossible for a jury to ignore. Angus Sinclair and brother-in-law Gordon Hamilton’s DNA was, it turned out, splattered virtually everywhere.

Sadly, it would take nearly 40 years - a generation - for the technology to arrive which would eventually lead police to the girls’ killers.

The first hint of progress came in 1988. The new wave of forensic science using DNA - providing detectives with a genetic profile of people who came into contact with a victim or could be shown to be linked to a scene of crime - was still in its infancy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSamples from Helen’s raincoat were taken to the lab, but forensic scientists failed to produce a profile.

And it would be another nine years before Strathclyde Police scientists were finally able to pinpoint a profile from Helen’s coat.

They didn’t know it at the time, but it was Gordon Hamilton’s. It was 1998 and every man who had been drinking in the World’s End between 10pm and midnight that night was tracked down. Mouth swabs were taken from criminals born between 1937 and 1960 who had a conviction for sexual or violent crimes and others who had been suggested as possible suspects. In total, 400 people were tested and samples placed against the DNA off Helen’s coat.

News that all were negative could have plunged the investigation into despair. Instead Detective Superintendent Allan Jones tried to view it as a positive - for it meant hundreds of potential suspects had been ruled out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd as time moved on, Helen’s coat was tested again, this time it revealed DNA from two men, one more dominant than the other, but still no matches on the police database.

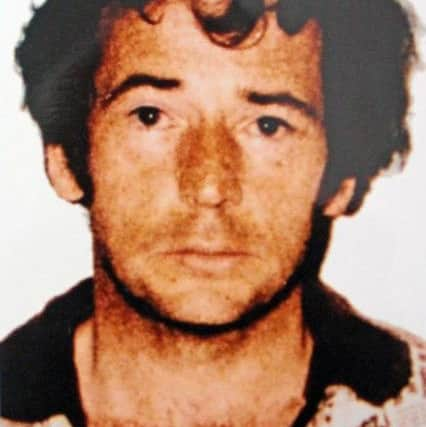

It was not until April 2004 that a different section of the coat stain was tested. The results were put through the criminal database once more - this time, the name Angus Sinclair appeared for the first time. Investigators recognised the name straight away. Sinclair had been arrested for the murder of Mary Gallacher in 1978 and had also killed an eight-year-old child. He had never previously come up as a suspect and had never been tested. However the odds were a billion to one that the DNA was not Sinclair’s.

Proving the other DNA belonged to Gordon Hamilton - Sinclair’s late brother-in-law - was to be much harder.

Some time after 1977, Hamilton had turned to drink - liver failure would ultimately take him in 1996 and he would die on a hospital floor. He was a painter and decorator who had helped a girlfriend decorate her Glasgow flat, putting up coving on the ceiling. A police team removed the coving where they found tiny traces of DNA. Along with family DNA it was enough to convince them it was linked to samples taken from Helen and Christine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was to be one more area in which forensic science would play a vital role - this time it involved Sinclair’s Toyota Hiace vehicle, converted into a caravanette.

He sold it in February 1978 - around the time a similar vehicle was being identified as possibly linked to the girls’ disappearance. It passed through several hands before ending up in Musselburgh and being scrapped in 1998.

Luckily, previous owners had kept photographs of themselves posing happily alongside the vehicle. In the images, the upholstery can be seen. Detectives tracked down a Morris Marina car which had been converted into a caravanette and found the upholstery matched. Eventually the fabric was traced to a Devon company specialising in vehicle conversions. Samples of fibres taken from Helen’s coat were an identical match to the fabric.

His earlier trial was halted when the Crown case was challenged by Sinclair’s defence who argued the prosecution had not presented sufficient evidence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it was the clever LED torch which would help seal Sinclair’s fate.

Using it for the first time in a Scottish criminal case, forensic scientists were no longer working in the dark. A large garment - such as Helen’s coat - offered many possible points of DNA contact. Crime-Lite suddenly provided a devastatingly accurate guide of where to take their samples.

Under its glow were revealed specks preserved within the twists of the knotted ligatures used to strangle the girls. Of major significance was the discovery of Hamilton’s DNA within a fold of Helen’s tights - proof, claimed the Crown, that it was deposited there while they were being used to strangle her. Later the High Court in Livingston would hear evidence that the chances of DNA that was found inside Helen’s coat belonging to anyone other than Sinclair, on the ligature made of bra and tights around her neck and belt used on Helen, were one billion to one.

It all added up to a raft of fresh evidence, and something to present to law lords now armed with new double jeopardy laws to enable an accused to be tried a second time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Without Crime-Lite, there would have been no trial two’, ” admits Lord Advocate Frank Mulholland - who was so impressed with the equipment that he made representations to senior forensic unit management to have it introduced to the Scottish labs.

And Detective Chief Superintendent Gary Flannigan, from major investigation team, describes the evidence it found on ligatures as similar to “a smoking gun”.

All that high technology, however, had to work hand in hand with something far more traditional.

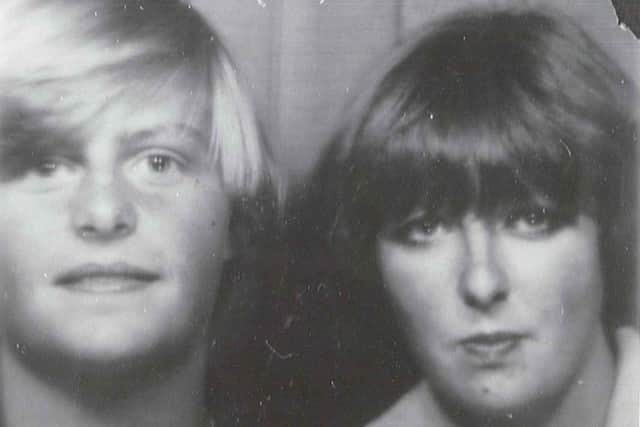

Helen and Christine’s hands had been tied behind their backs, Christine’s using two reef knots, Helen’s with granny knots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRoger Ide, a forensic specialist with 30 years of experience of looking at knots and bindings, was called in. And what Helen and Christine’s ligatures told him was it seemed likely that not one, but two people were involved in tying them.

A simple knot versus a more complex one. One which required little skill to tie, the other requiring some expertise, suddenly it seemed more likely that more than one person was present.

Even the way the girls’ hands were bound - Christine’s by her own tights - revealed to detectives more of what happened that awful night.

After years of speculation over which of the girls was first to die, knot analysis gave up another secret: a three-inch stretch of tights between each of Christine’s wrists suggested she had struggled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHelen’s wrists, however, were tied close together, no gap, a sign that, resigned to what was happening, perhaps in shock, she did not struggle.

The story behind the most perplexing case of a generation had been unravelled.

• This article originally appeared in the Edinburgh Evening News on November 15, 2014