Edinburgh's unbuilt Inner Ring Road

Unlike inner Glasgow, the centre of Scotland’s capital city is motorway-free, but it could have been very different.

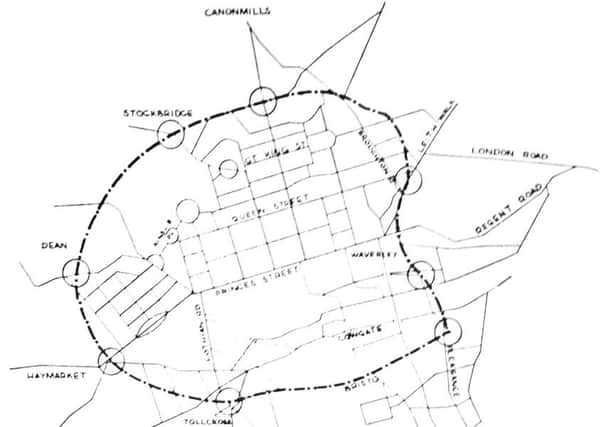

Extensive changes were first mooted in 1949 when planning experts Patrick Abercrombie and Derek Plumstead drew up the infamous Civic Survey and Plan for the City & Royal Burgh of Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReferred to simply as the Abercrombie Plan, the document put forth some rather bold recommendations which included the complete clearance of inner city districts such as Leith, Gorgie and Dalry, with a view to creating new ‘industrial zones’, a freight railway under the Meadows, the birth of new outer city developments and a controversial rebuilding of Princes Street.

Also suggested, was an ambitious road proposal to carve an inner city bypass through the Capital in a bid to cure its growing traffic woes.

Needless to say, the proposal was not universally popular.

‘An inner ring motorway’

In 1963, the once outlandish notion of a motorway being driven through central Edinburgh suddenly became extremely likely when the Town Council gave a new highway plan the green light.

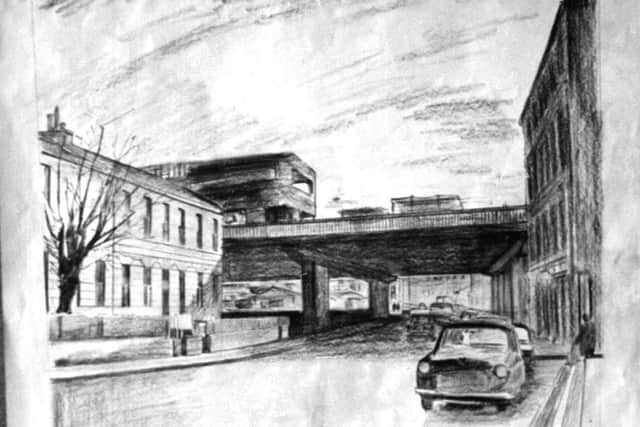

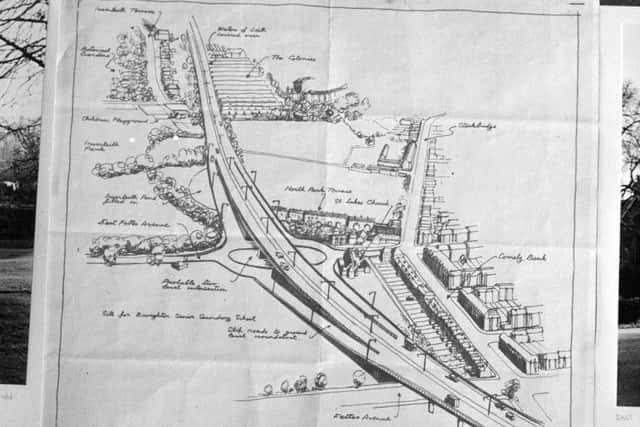

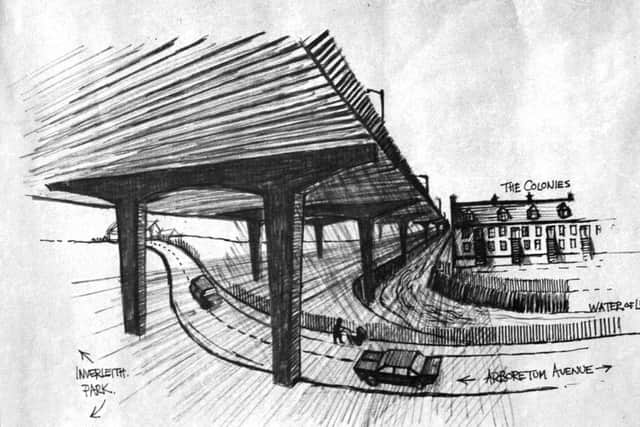

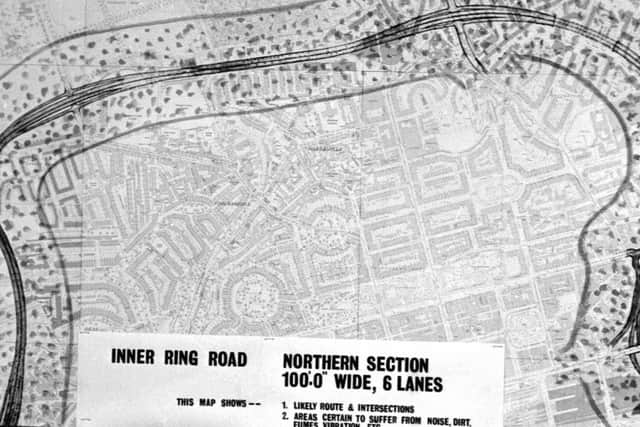

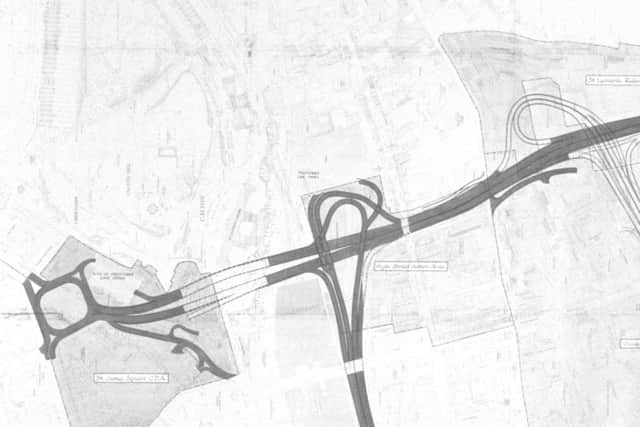

Drawings show that the new six-lane motorway incorporating bridges and flyovers would run through Haymarket, the Dean valley, Stockbridge, Canonmills, Leith Walk-York Place, Pleasance, Bristo, Tollcross, before ending up at Haymarket again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe route meant that much of what is today safely within Edinburgh’s World Heritage Site would have been wiped from the map. For example, the section between the top of Leith Walk and the Pleasance meant tunnelling beneath Calton Hill before splitting the Old Town in two at St Mary’s Street. Hundreds of historic buildings would have been toppled as a result.

Likewise at Haymarket and Tollcross, where two huge interchanges would have required masses of open space.

Through the Dean, Comely Bank and Stockbridge, there would be an elevated roadway six lanes wide and 20 feet high which would have encroached Inverleith Park and prompted its famous duck pond to be filled in.

One map marries ordnance survey data together with the proposed route to display the extent of the motorway’s footprint and how much of the surrounding area would be directly affected by noise, dirt, pollution and vibration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLobbyists and heritage campaigners were appalled at the prospect of losing so much of their city to modern infrastructure.

Writing to The Scotsman in 1967, the Earl of Dalkeith was adamant that an inner ring road for Edinburgh was out of the question: “This is a national issue of international significance in that it drastically affects the whole character of Scotland’s capital city as one of the world’s most outstanding and beautiful masterpieces of urban planning and architecture.”

Despite the opposition, however, the issue would not go away and renewed proposals continued to be drawn up well into the seventies.

Stuart Baird, transport history expert and curator of popular website, The Glasgow Motorway Archive, helps explain the reasons behind the controversial plans: “All British cities in the post-war era focused their attentions on building motorways. Everyone knew traffic flow was on the up and most cities were looking at what they had to do to improve things.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdinburgh’s process would have been similar to Glasgow, but the difference was that Glasgow had a far greater number of areas earmarked for slum clearance, it was therefore far easier to clear the land and build the roads.

“There are elements of the Edinburgh plans that do make sense, such as the outer ring road and obviously today Edinburgh is not an easy city to move around.

“But it’s probably a good thing that it didn’t happen, due to the damage that it would have caused.”

Stuart goes on to reveal that, at one point, the Scottish Office had set aside 5 to 6 million pounds for stage one of Edinburgh’s motorway.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, the city’s continued reluctance to proceed meant the money ended up going to Glasgow to build the Renfrew Motorway instead.

Edinburgh’s staunch conservatism and innate desire to protect its built heritage meant that it would not follow Glasgow’s lead.

Today, the City Bypass, constructed throughout the eighties and nineties, and a few isolated examples of dual carriageway built upon former railway lines at Dalry and Portobello are among the few examples of motorway to be found within the Edinburgh city boundary.

Had the motorway proposal gone ahead as planned, it is doubtful that Edinburgh’s Old and New Towns would have been awarded the joint World Heritage title they received in 1995.