A true account of arsenic poisoning in Victorian Edinburgh

The 19th century witnessed the birth of the age of consumerism, and a race among the growing middle classes to chase the latest fashions and trends. Victorian homeowners turned to popular style bibles such as Cassell’s Household Guide; to keep them up to date with the latest fabrics, designs and colours.

Scheele’s Green

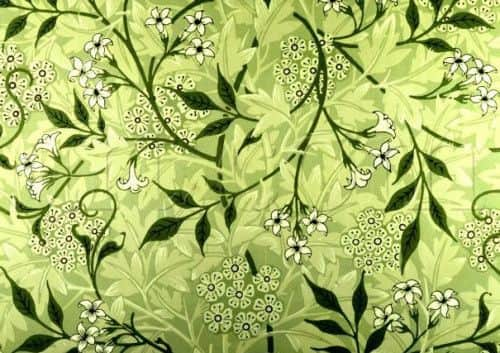

In the early part of the century a rich, vibrant green named Scheele’s Green emerged. The colour proved massively popular, and by the middle of the century it was used in the production of everything from wallpapers, paints, and candles, to clothes and children’s toys.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHorrifyingly, many of the major manufacturers of Scheele’s Green were deliberately loading it with lethal amounts of copper arsenite.

Arsenic possessed a unique property that enhanced certain pigments, preventing dyes from fading. Despite the fact it was known to be toxic, arsenic was a wallpaper manufacturer’s dream. Firms played the line that as long as you didn’t ‘consume’ a product laced with arsenic, you’ld be perfectly safe - a disturbing fallacy which would last decades.

Arsenic in wallpaper

Sales of wallpaper soared in the 19th century from around 1 million in the 1830s to over 23 million by 1860, and, for many, Scheele’s Green was the colour of choice.

As demand for wallpaper increased, so did mysterious reports of homeowners suffering slow, agonising deaths. Households affected by damp were a real hazard; toxic gas released by moisture compounding on the walls literally killed thousands of people - including, some historians claim, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHeat also had a similar effect, putting those with gas lighting and coal fires at considerable risk. Millions of Victorian livingrooms had become veritable deathtraps.

The scale of the problem was horrifying, as Alison Matthews David, author of ‘Fashion Victims: The Dangers Of Dress Past And Present’, explained to The Scotsman in 2015: “Green wasn’t a colour that was easy to dye. “Arsenic didn’t fade and looked bright under lights. It was stunning and became hugely popular in clothes. A ball gown would contain enough arsenic to kill 200 people and a hair wreath 50. The amounts used were lethal.

“It was used in wallpaper and food colour too and there were reports of people in Glasgow being poisoned by the icing on cakes.”

Recent data reveals that arsenic levels found in hair samples of the average middle class Victorian were around 100 times higher than they are today.

Symptoms

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArsenic poisoning was not so easy to identify. Some of its core symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and muscle cramps were often confused with the hallmarks of cholera. This striking similarity delayed scientific progress in identifying the correlation between the recent spate of illnesses and the levels of arsenic present in people’s homes.

Ban

It took until the 1870s for authorities in England and Wales to wise up and condemn the use of arsenical wallpapers. While never officially banned, the practice of adding arsenic to wall hangings received such universal bad press that leading manufacturers began to include guarantees that their products were “arsenic-free”.

However, officials in Scotland were much slower to act.

An Edinburgh account

In March 1882, a fascinating heated exchange developed in The Scotsman newspaper between an experienced Edinburgh paper stainer, John McCrie, and leading chemist, Dr Stevenson Macadam.

On 27 February, Dr Macadam attended the Royal Scottish Society of Arts on George Street, Edinburgh to read a paper which publicly condemned the use of arsenic in commercially-produced paper hangings. Macadam believed that firms should be held to account for putting the public at risk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndustry representatives, such as McCrie, were absolutely livid, and on 1 March, the paper stainer penned a letter to Macadam via The Scotsman, pouring scorn on his rather controversial claims: “Are arsenical or other poisonous ingredients now used by painters and paper-stainers generally injurious to health? I have no hesitation in answering in the negative. It appears to me in the poisoning of the public mind lies the greater danger.

McCrie continued: “It is neither the desire nor the interest of the paper-stainer or the painter to shorten the lives of his customers.”

Dr Macadam responded explaining that manufacturers in other nations had recognised the inherent dangers of arsenic infusion and that “equally pleasing and artistic tints and designs” could be obtained without its employment.

On the 8th of March, a colour manufacturer based at Jane Street in Leith joined in the debate: “We can only say that, unless scraped off or eaten, they (the wallpapers) are perfectly harmless.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Macadam knew this statement couldn’t be further from the truth: “In the majority of poisonous wall papers the colours are more or less loosely attached to the paper and the mere dusting of the wall with a cloth or brush will detach some of the colouring agent.”

In a letter dated 11th March, John McCrie rejoined the discussion to focus on an earlier Macadam remark that, unlike Scotland, many English wallpaper firms were now adhering to a revised advertising policy confirming their products to be free of arsenic.

McCrie dismissed this as scaremongering: “The fact mentioned by Dr Macadam, that some English firms announce they are prepared to guarantee all their wall papers free from arsenic only proves this public scare is more prevalent in the south.”

The paper stainer then poked fun at Macadam when he said: “As I have just had my parlour re-papered with green paper, Dr Macadam will be at no loss to explain my silence in future”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, not everybody disagreed with Macadam, and contrary to McCrie’s belief there had been victims in the Capital.

On the 15th of March, The Scotsman published a letter from an anonymous Edinburgh resident: “About 18 years ago my dining-room was papered with a flock paper, green and gold. The colour was bright and pleasant to look at, and no fault could be found with it in that respect.

“As the winter progressed, my wife and I could not understand how it was that by nine or ten o’clock at night we always felt sleepy and uncomfortable, and my eyesight began to be affected to such an extent that a fear crept over me that I was beginning to lose my sight.

“A friend suggested that the wall-paper very probably had something to do with it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The paper was accordingly subjected to a test and arsenic was found to have been largely employed in giving the paper its fine bright colour.

“The room was at once abandoned and another occupied, when the whole of the symptoms disappeared.

“Dr Macadam deserves praise for drawing attention to the subject, and thereby saving many from the injurious consequences.”

Within two years of the Macadam debate the first advertisements promoting non-arsenical wall-papers started to appear in Scotland.

At long last, Scottish firms were recognising the deadly threat posed by the presence of arsenic in commercially-produced wallpaper.