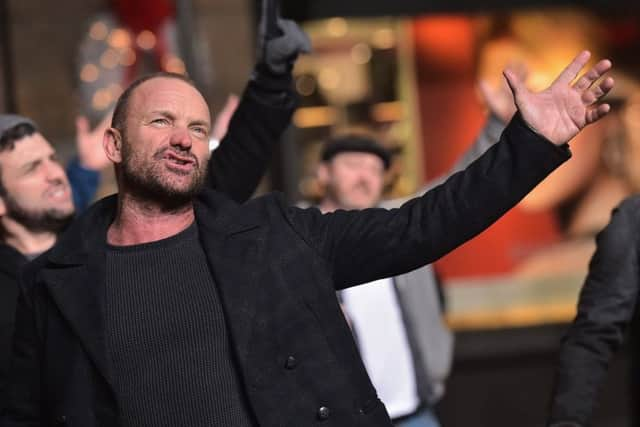

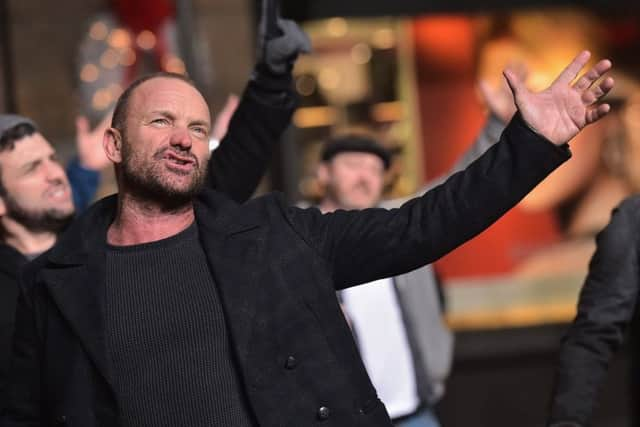

Interview: Sting's new musical sails into the Capital

Yes, Sting, real name Gordon Sumner, just don’t call him that, was about to give an intimate performance to launch a new production of his Broadway musical, The Last Ship, which sails into the Festival Theatre this June.

The Dockers’, an appropriate setting, is one the singer admits makes him feel at home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It does feel like home actually,” says the 66-year-old, adding, “when I caught sight of the ships in the water as we came in, I got emotional. There is something about a ship that excites me; a symbolism that is very powerful.”

Explaining, he continues, “When I was a kid growing up, looking at the end of my street I’d see this massive cathedral of steel. Then, to see it launched... with such noise... yes, it is a very powerful symbol for me, and not all positive; the demise of the shipyard and the demise of my parents health was very symbolic.”

Born and brought up in Tyne and Wear, under the shadow of Wallsend’s shipyard, The Last Ship is consequently very close to the singer’s heart.

Semi-autobiographical, it tells the story of Gideon Fletcher, a sailor, who returns home from sea to discover the ship-building life he left behind in chaos.

The yard is closing and no one knows what will come next.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

With the engine fired and pistons in motion, picket lines are drawn as foreman Jackie and his wife Peggy fight to hold their community together in the face of the gathering storm.

The musical premiered in Chicago in 2014 before transferring to Broadway the following year, a decade and a half after Sting had first been inspired to revisit his early days.

“I wrote an album in 1990 called The Soul Cages, which was about the shipyard and about my parents dying...” he says, “so yes, I have lots of mixed emotions about the shipyard.”

If The Soul Cages was the starting point for The Last Ship, the Gdansk shipyard strike and formation of Solidarity by Lech Walesa in 1980 along with the Clyde shipyard work-in of the Seventies led by Jimmy Reid provided the meat for the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

“The Soul Cages always had a theatrical component but it wasn’t until I read about the guys in Gdansk who, though out of work, started to build their own ship just to get themselves back together, and the stories of Jimmy Reid that I thought, ‘If I can weld those stories to my town, we have an allegory for that time and can give a voice to people who had never had their stories told before.

“Not in my time anyway,” he says, holding up a copy of Voices of Leith Dockers, by Ian MacDougall, which he had been given earlier.

“When the guy gave me this book, it was wonderful. I recognise these people from growing up.

“They had such pride in their work. That is what I wanted to bring to this play.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

“It was hard, awful work and yet they could look back down the hill every night and say, ‘We built that thing... one of the biggest ships ever built, and we built it.

“In modern society we don’t make much with our hands anymore, so what do communities do when they are suddenly told they are irrelevant to the economy.

“For me that’s a terrible poison to live with. I don’t know the answer, but I know that the story has to be told and that maybe, within that narrative, is some way out... what they do in the play is they occupy the yard, finish the ship, and sail it off themselves.

“It’s a grand gesture to say ‘This who we are. We are proud of who we are. Deal with us’, but it is no more than a gesture.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResearching the piece brought Sting home to Wallsend, a visit he obviously found traumatic as he describes the emotional turmoil it evoked. After all, like all dock lands, life was hard and poverty rife.

“I wanted to escape, I really did,” he says. “The only rich people we saw would be the ones who came to launch the ships; I remember very particularly that once a year the Queen Mother would come along in a big Rolls Royce with out-riders and everything...

“I would think, ‘I want to be in that car. I want a life outside of these streets. I don’t want to work in the shipyard or in the coal mine at the other end of town.’ I had a bigger dream.

“I dreamt I would be a musician and I must have dreamt it awfully hard because that is what happened and I am eternally grateful for that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But I also feel the need to honour where I come from, to pay a debt if you like, because those people, that community, made me who I am.”

“The ship, again, is a symbol for me, those ships left that town and never came back, they were too big to come back.

“For me, I said ‘I want to be on that ship, in that car. I want a bigger world. I deserve a bigger life as much as anybody’.

“It was a seed planted in me, an ambition to escape where I came from, but there is guilt attached to that too, a survivor’s guilt; my town is still... the ship yard is just a hole in the ground and there is nothing else.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe considers for a moment, before continuing, “I went back it was like going on a ghost train. There’s a lot of hurt there for me. It really wasn’t an easy thing to dredge up, a lot of pain, but I’m really glad I did.

“It is good therapy to accept who you are, where you come from, to forgive your parents...

“My parents were really young. My mum was 18 when she had me, my dad maybe 22, and they died young, so I never really got the chance to thank them, or forgive them, or go back to them. In a way, this work is my rather extravagant mourning for my parents.”

On Broadway, Sting became even closer to his creation when he found himself taking over from Jimmy Nail (“He was my muse, I bounced ideas off him”) as foreman Jackie. Did he ever envisage being on stage in his own musical?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“No I did not,” he declares emphatically, “but it was a tough subject for Broadway audiences to embrace. Most Broadway shows are plays or musicals they know already. The hardest thing to do there is an original piece with a serious core, although the people that saw it, loved it.

“The producer said, ‘You need to go on, we need to sell more tickets’. I asked who I could play and he replied, ‘Take Jimmy’s part.’

‘I’ve got to throw my friend under the bus? Is this what showbiz is about?’ I said, and he said, ‘This is Broadway kid, you do it.’

“I made sure he told Jimmy,” Sting grins, “and I loved it. I only had half an our with the stage manager before I went on but I already knew it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Jimmy said he’d give me notes every night. After my first night he said, ‘I’ve just got one note for you; be taller’,”he laughs.

With casting for the new production yet to be announced, he adds, “I think it will resonate well with the people of Edinburgh. I’m just dying to see how it goes down here.

“It’s a more political show than it was on Broadway where we favoured the love story more. “Now we have shifted to the left, the love story is still there but the emphasis is slightly different. It’s a simpler story.

“I don’t think work is ever finished... you know, a song is never finished, you are always rewriting it, always adjusting incrementally. So the play is like that too. I’ll be there all through rehearsals, on call to change a verse or lyric, to write a new song if need be, to fix what’s wrong, and I’ll do that throughout the tour.”

He’s looking forward to return to the Capital too.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ll be here on opening night,” he reveals, “and intend to spend some sightseeing too.”

A trip to see what remains of Leith Docks, it seems, is certainly on the cards.

The Last Ship, Festival Theatre, Nicolson Street, 12-16 June 2018, 7.30pm (matinees 2.30pm), £22-£42, 0131-529 6000