Brian Monteith: Will Nats and Remainers ever learn their lesson?

That is called experience, which rarely comes from getting things right but from learning from your mistakes and remembering not to repeat them in the same or, more likely, different circumstances.

Politicians regularly make mistakes because they rely upon poor assumptions that are found wanting. People, who are of course individuals and can make their own minds up, do not always behave as politicians predict or expect. When people don’t behave as assumed they are often blamed, but it is more likely that a politician’s poor assumptions were unchallenged wishful thinking. Examples of mistaken assumptions in politics are always with us, and when politicians do not learn from them they are destined to repeat their errors and pay a political price – a fall in support to the point that only die-hards remain lashed around those false assumptions and their beliefs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

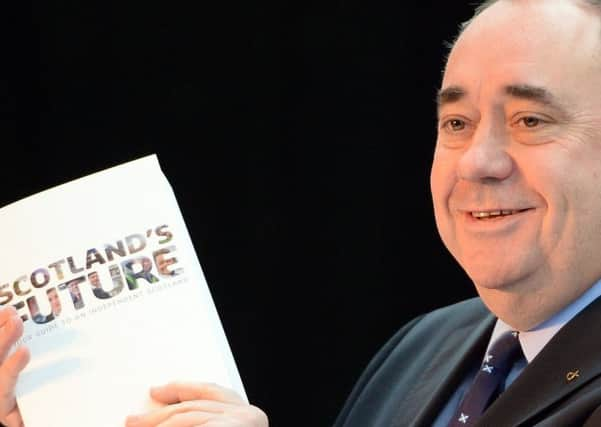

Hide AdTwo political groups are having their sanctified assumptions severely tested at the moment; Scottish nationalists of the Sturgeon strain, and devout adherents of the European Union. In the 2014 independence referendum, the SNP offered its now infamous White Paper on how an independent Scotland would work and what it would look like. It soon became apparent to those who studied it, even loosely, that it was riddled with false assumptions.

The White Paper gave Unionists of every colour the opportunity to explode the false nirvana that it offered. This helped create enough doubt in the minds of voters that it was better to stay with the UK, despite its faults, than risk a paradise that would be lost from day one.

Subsequent events – with an oil price collapse that have cut tax revenues – and higher Scottish taxes, despite rising UK government financial transfers above and beyond the fall in oil revenues – have proven the SNP’s assumptions to be wildly wrong. Two years later and we had another referendum, this time on the UK’s membership of the European Union, and we saw more false assumptions being rolled out. A particular favourite, especially in Edinburgh, was how our universities would suffer from a drop in EU students, as somehow they would be discouraged to come here. There was, in fact, no reason that such an outcome would follow, for nobody, including Brexit supporters, was advocating it. Thanks to the uncertainty caused by such hysteria applications from foreign students did indeed drop last year but have this year bounced back to a record level.

More than 100,000 foreign students have applied to enrol at UK universities in the autumn, rising 0.3 per cent to 37.1 per cent of applications. EU applicants rose by 3.9 per cent to 43,510 and other foreign students rose by 11 per cent to 58,450 – exposing as unfounded the assumption that EU students would stop coming to the UK. What we are now witnessing is the realisation that Brexit does not change the value of a UK university education. As was argued during that referendum, with no EU universities in the World’s top 30 – except for six from the UK, including Edinburgh – the UK should continue to be a magnet for international students.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdinburgh’s foreign student population is not at risk – unless our universities make their own misjudgements that damage the reputation of their teaching. The campaigners for Scottish independence in 2014 and for remaining in the EU in 2016 both relied upon false assumptions that did not fool the electorate. Unless those false assumptions are dropped and replaced, Scottish independence and a trans-European state will both remain unachievable. As both campaigns now decline neither is a prospect in the near future, and thank goodness for that.